Welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter about things I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If you haven’t yet, make sure to sign up so you don’t miss an issue. I’ll be publishing once a week on Saturday or Sunday mornings.

And now, sports.

The National Basketball Disassociation

The sports media world has spent most of the month of December discussing NBA ratings. They are down. A lot. There are lots of theories about why.

All that matters, though, is that fewer people are watching games.

Stratechery’s Ben Thompson noted this week that part of the league’s current public stance on why the ratings are down is that their games are on cable, not broadcast. This is problematic.

The problem with blaming cord-cutting for the NBA’s decreased ratings is that the entire reason why the league gets the huge amount of money it does, first from national networks and then from regional networks, is because its product is a reason to subscribe to the traditional cable bundle. To suggest that traditional cable subscribers are the horse pulling the NBA cart is to massively diminish the NBA’s actual value, which is the exact opposite — being the horse that pulls the traditional cable bundle cart.

And so as Ben alludes to, it is starting to look like a lot of the NBA’s excess value that accrued to owners and players was created by people who didn’t want to watch the NBA at all.

A large part of the cost of the cable bundle has been driven up by the fees paid by distributors to channels like ESPN and regional sports networks. Those costs were passed along to subscribers, many of whom didn’t want to watch sports anyway. It’s just that these people had to pay for the sports to get cable that offered them other things.

But now, those sports-indifferent customers are increasingly offered ways to avoid those costs. This is cord cutting in a nutshell.

The NBA, like any content owner, has a few options. They can distribute games more widely, which the league is doing through League Pass and other avenues. The league could also push to have more games on broadcast networks like ABC, a move that — all else equal — gets a game in front of more viewers. More viewers makes advertising against these contests more appealing to advertisers.

But the long and the short of the NBA’s cable problem is that customers don’t have to pay for the NBA to get other content offered on cable. And even the NBA fans who do have cable apparently aren’t watching as much. So the league might now be facing the unexpected reality of its product having less value than previously estimated.

In 2014, the NBA announced a new nine-year, $24 billion deal with ESPN and TNT. This contract took effect in the 2016-17 season, so we’re in year four of nine right now. On the one hand, the league has time. On the other hand, there are only five more seasons to figure this thing out. And cord-cutting is not decelerating.

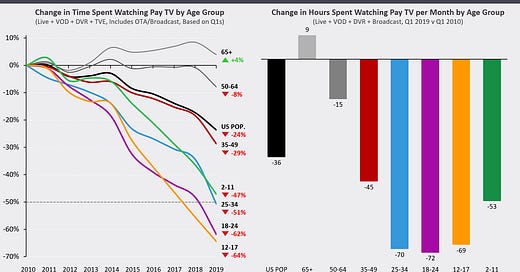

Back in November, Disney CEO Bob Iger said of cord-cutting trends, “I don't know what the floor is, nor do I think the floor is anything close to being in sight.” And it’s obvious why: the speed with which young people have stopped watching TV is almost beyond belief.

Sameness and bigness

In two weeks, the college football playoff semifinals will take place.

These games pit the four best teams in college football this year (#1 vs. #4, #2 vs. #3) in televised spectacles that this year will be held in Atlanta and Phoenix. The winners will play in New Orleans in early January for the national title.

In 2012, ESPN agreed to pay $5.6 billion for 12 years of the college football playoff. The playoff started back in 2014. We are now halfway through that agreement. When ESPN signed the deal, they had right around 100 million paying subscribers; now, that number is closer to 85 million.

Reports this week suggested that an 8-team playoff could be coming, potentially before the end of this current TV deal. I have little doubt the playoff will eventually be expanded to 8 teams. Without going through the nitty gritty of why competitively 8 makes just as much sense as 4, what sports and their relationship to potential television audiences have never shown is restraint.

So but the whole point of the playoff is that it settles, once and for all, the arbitrary and frustrating system previously used by college football to pick its national champion.

It is a system that went from a bunch of coaches who didn’t watch other teams’ games voting on a national champion, to a bunch of media members that didn’t watch the games voting on a national champion, to a computer system that also seemed to not really understand games picking the two teams that would play for the national championship, to a four-team playoff where everyone gets to go home happy.

Since its inception and including this year, 24 individual teams have been selected as semifinalists for the tournament. Of these 24 teams, 17 are from schools that have been selected for multiple tournaments. Throw a dart at a college football playoff and it’s likely that more than half the teams in the field were there the year before.

This year’s tournament, for example, has 2 of the 4 teams from last year. Last year’s tournament had 3 of the 4 from the year prior. You can do the whole exercise yourself here, if you’re so compelled.

It seems, then, that in striking a big TV deal with ESPN that made this tournament to find the “right” champion possible, the sport has become yet another avenue through which we experience the rich-getting-richer dynamic that defines American life today.

The major boosters, alumni, students, and the deeply-invested fans of the sport had spent decades clamoring for a fix to its national champion problem that had always been sitting right there in front of them: have a tournament, best team wins. It’s the solution every major North American sport has adopted to decide a champion.

But the competitive upshot is that the level of near-excellence needed to qualify for the tournament has been codified and only about 8 or 10 programs ever have a chance. The rest of the season has become utterly forgettable and meaningless.

And so now that college football has come around and found the “right” way to pick their champion just like every other major sport, it has become just like every other major sport. And being just another major sport has gone from the safest bet in the content world to a seemingly tenuous position. Quickly.

There will be ratings

As my Yahoo Finance colleague Daniel Roberts knows, anything ever written about ratings is called wrong by some invested party. There is, seemingly 100% of the time, an explicable reason for any ratings change that leaves a league, a network, an analyst saying: there is no problem here.

And yes, the ratings for the college football playoff have generally been good. They will probably continue to be good. I don’t have a strong view on what the ratings trajectory could, should, or will be for the college football playoff.

But blip or not, the beginning of this NBA season has made clear that something is changing when it comes to the habits we’ve formed around consuming content. And the value that’s been ascribed to certain content by the market is now facing pressure from a deeper, more liquid market. Sports leagues negotiating with a handful of cable channels for their rights package once a decade has morphed into sports league negotiating with millions of consumers on a daily basis.

And so the made-for-TV solution to finding a champion that college football has found itself pursuing seems to have a potential problem: it’s made for TV.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This.

If you liked what you read, share it with a friend and make sure to subscribe.