Can we trust our lying eyes?

The economy is hurting. Lots of cars on the road doesn't make that not true.

Hello and welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter from Myles Udland about stuff I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If you’re new here, thanks for signing up!

If someone sent this your way or you found this post through Twitter or other channels, make sure to sign up below.

We publish every Sunday. Except for today, which is a Monday that feels like a Sunday.

And now, about the recovery…

I hate to see internet friends fight.

Or rather, I hate to see one person I like on the internet dunk on another person I like.

But I think Quantian’s tweet this week about how the anecdata has gotten a bit unruly is a great summation of where The Discourse stands as we wrap up the summer of 2020.

And while I’ve become more of a reopening optimist during the summer as my own life normalized, economic data don’t support anything other than continued emphasis on the depths of this recession, the urgency of a fiscal response, and the looming fiscal cliffs that Nathan Tankus has outlined as a feature, not a bug, of the current appropriations process.

Now, there is definitely a sense that the world is coming back online.

I have driven in traffic, played golf with strangers who think COVID is a hoax, agreed with those who say the right frame for this next economic phase is long Planet Fitness and short Peloton.

This chart from JPMorgan — which everyone on Finance Twitter probably has bookmarked and refreshes daily — is at the crux of most bull cases.

This chart suggests all sorts of things about whether a failure to extend the full CARES Act was as large of a policy failure as myself and many others thought it would be, whether the economy is going to falter in the fourth quarter and into 2021, and whether this pandemic-induced depression will be remembered as such.

This chart, in other words, appears to be Definitely Good.

But is it?

Because it’s just one piece of data that looks not-terrible. And a flawed piece of data at that. As noted above, part of what is helping this data stay so stable is that many places aren’t taking cash. Guillermo Roditi Dominguez at New River Investments also flagged an issue with this data last month, noting that it does not capture spending from prepaid debit cards provided as part of the PUA program.

So but right now, the bar for not-terrible data is quite low. Some data coming in less than terrible, however, is not the same as things being good.

Take last Friday’s jobs report.

Excluding Census-related hiring, the economy added about 1 million jobs last month and the unemployment rate fell to 8.4%. Morgan Stanley economists said the jobs report “was solid and gains were broadly based.” The team Oxford Economics, however, called the report “half empty, not half full.”[1] This divide among mainstream economists over whether Friday’s jobs data was good or not is a reminder that we cannot look past the simple, jarring facts about our economic moment. Facts which remind us that as of August, the economy is down 11.5 million jobs from February and 50+ million people have filed for unemployment insurance since March.

And we cannot ignore the economic damage outlined elsewhere in this same jobs report. Damage that suggests the crowded highways, busy outdoor restaurants, and bustling bougie vacation retreats for the unaffected upper middle classes of major metros reflect an alternate reality about the economy right now.

Lakshman Achuthan at the Economic Cycle Research Institute outlined Friday the loss of jobs in the service sector, the sector which accounts for 70% of economic growth and 80% of employment. And the numbers are grisly.

In a sector of the economy that employed just over 130 million people at the end of 2019, employment has dropped 9%.

If you’ve gone full Markets Brain, you’ll only be able to see things in terms of percentage change and rates of change. This will serve you well when trying to allocate money to sectors and individual businesses that are growing. It will serve you less well when trying to grasp the scope of the damage done to the labor market and the pain still to come if the half-measure approach to healing this recession continues apace.

Because when a business sees earnings drop by 9% the entire decline might be explained by foreign-exchange adjustments. It may be worth ignoring this drop. But when employment in the services sector drops by 9% it means 11.7 million people — or the entire population of Ohio — are out of work. Not the working-age population of Ohio, but every man, woman, child, and senior in the state would be sitting at home doing nothing. This is the 7th-most populous state in the country.

The economy may be measured in percentages and aggregates but life is lived on a nominal and individual basis. And we must not be content to let tens of millions of workers fall out of the labor market because of the cost.

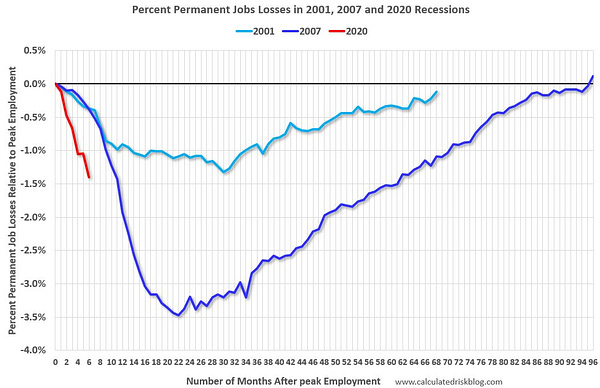

Another troubling chart that emerged out of Friday’s report comes from Bill McBride at Calculated Risk, who shows us the speed at which job losses are becoming permanent. Tens of millions of unemployed workers were classified (or, in the eyes of some economists, misclassified) as temporarily unemployed back in April and these numbers are coming down as the economy recovers. But the number of permanent layoffs is rising sharply and rising faster than we saw during either of the last two recessions.

Parking lot tents across America may be full of diners on a summer Friday night, but what the full tent doesn’t tell you is that the restaurant is still operating at 50% capacity because if anything close to the full front- and back-of-house staff were brought back the money bleed would happen even faster than is already underway.

And when you’re venturing out on a Saturday afternoon and the road seems as busy as it would’ve been in the Before Times, what you don’t know is how many people driving those cars are unemployed or underemployed workers frustrated at the lack of clarity about how their kids are going to get back to school safely, when their hours will get back to full-time, and what happens when the winter comes. The jobs report suggests quite a few.

So the stock market might tell us that these crowds out in the world are the leading edge of the next economic boom. Well, not might. That is what the stock market tells us to believe. And it may well be true.

But it also doesn’t have to be true for the stock market’s boom to be justified. All investors really want are more profits from Apple and Facebook and Google. A desire that can definitely be fulfilled amid an extended recession where the poorest Americans are left behind as a matter of official policy. Just look at the 2010s.

So if there is a disconnect between stocks and the economy it is only on the level of which disparate themes our brains bring together as evidence of something like a recovery. WFH trades and the market’s newfound excitement about software businesses and anything related to a new economic order that elevates recurring revenue and de-emphasizes any kind of human interaction does not serve as a replacement for the 11+ million unemployed workers in the economy’s most important sector. Rising asset prices merely cover up this damage with spackle and fresh paint. Just at higher margins.

To some, the end of the summer of 2020 might seem almost normal. There are surely those asking why it isn’t more normal. There is a strain of exasperated conversation you’re likely to get stuck in these days if your friends — like most of mine — are over-educated sub/urban yuppies who want to do the right thing but are also tired of doing the right thing.

Everything is crowded, you’ll say. Are people not worried about COVID, someone else might ask. We need to start thinking about opening up even more, another suggests. But we still don’t know the long-term effects of COVID, the most correct person in the group reminds us.

And around in a circle this conversation goes for the kind of millennial that is far from a Trump-loving dingus who shitposts memes on Facebook and attends boater rallies but who also thinks we’re being too cautious with our current reopening plans because we can’t be quarantined forever.

Though of course, we haven’t been quarantined or locked down for months.

Since May, in just about every part of the country that isn’t the Tri-State Area or LA/SF, you’ve pretty much been on your own. Most all businesses have been allowed to operate under loose, barely-enforced restrictions and it is up to you, the private citizen who is not a medical expert, to use your best guess at what is safe in order to avoid getting sick. Contact tracing is barely existent. Testing policies are haphazard. It is still, six months into the pandemic, unclear just what the extent of the outbreak is right now or has been over the last few months outside of work from folks like Youyang Gu.

And so with no good answers from authorities who should offer them, we have entered a golden age for anecdata about the state of the U.S. economy that I think is teetering on the edge of full-out denialism about the recession, the recovery, and how lawmakers and other officials ought to proceed with what happens next. And we’ve reached this moment believing what we see instead of what a sum of the economy’s parts tell us. We are in this position not because of economic data but in spite of it.

Because what the data really tell us is we shouldn’t believe our lying eyes. We shouldn’t trust that it looks like things are reopening with vigor, that the world appears to be. getting back to “normal,” that this crisis seems to have turned out to be temporary.

The economy is operating so far below capacity that we can’t help but make excuses for how “normal” things around us might seem. The empty streets of March and April were so out-of-a-disaster-movie surreal that the presence of other people walking, driving, and laughing outside their homes still seems novel and good and like an improvement. But the distance between where we are, where we were, and how we’re going to get back is an economic valley this country hasn’t traversed since the 1930s.

The collective psychological trauma we all endured in the spring of 2020 is only beginning to be understood. But the first place these scars are showing up is in the economy, in what we are choosing to see and not see about the ongoing crisis.

Writing this letter surprised me. I began the letter ready to make a case for the economy’s success. And I ended up here.

As noted above, I’ve grown more bullish — considerably so — over the course of the summer. Maybe it’s just because my job is to stare at the stock market and then tell people what’s going on. Hard to be depressed when the stonks hit record highs all the time. But it also seems that a vaccine will come sooner rather than later. Meanwhile, the sports world continues to chug along and, save for baseball, these institutions have outlined that things can go on in a modified but still satisfying way if we throw the right resources at the problem.[2]

I’m also bullish on NYC, on cities in general, and on the world in 2022 looking like the world in 2019 instead of a kind of Blade Runner dystopia that the techno-futurist set — who are now allied with the misanthropic suburban opinion columnist set — currently imagines. Either the decline of New York City as described by the NY Post is not real and the city’s rebound lags whatever utopic moment Post readers believe has broken out in transit-adjacent suburbs, or the suburbs will soon be in crisis.

This relative bullishness, however, falls into the Deux ex Vaccina trap. Meaning that just because I’ve allowed myself to relax because my circumstances are okay doesn’t mean it’s feasible for everyone to just sit around with no real plan for dealing with the virus while we wait for a pharmacological bailout.

Everyone knew this wasn’t a credible strategy for coping with the pandemic when the White House made this their official policy in the spring. And I should be equally as dissatisfied adopting this tactic for myself now. Especially when the data are so clear about the urgency of this economic crisis.

What we see in front of us is not what’s true for all of us. Be it a pandemic, a depression, or otherwise.

And thinking only about ourselves paints a picture more deceiving than what would otherwise appear in our apertures.

[1]: And while we could do a whole newsletter about the value of U-3 in this kind of environment, the value of U-3 in any environment, and how to interpret any one month’s jobs report, we will not. But we could. U-6, by the way, stood at 14.3% in August and while this measure of unemployment has been used as a political cudgel to an unprecedented and frankly unacceptable level in the last decade, Gary Cohn loved talking about U-6 when he was NEC director 🙃.

[2]: Then again, it is a massive indictment of government at all levels that only professional athletes are getting access to anything like the processes needed to get the gears of the world turning again.