Welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter about things I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If you were forwarded this email or haven’t signed up yet, make sure to do so here so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday morning.

And now, a newsletter sort of about newsletters.

In the world of stock market commentary, you often hear versions of the idea that no one knows anything. This is the extreme efficient market hypothesis (EMH) idea that would say offering an answer to — or commentary on — the question: “Why is the stock market _______ today?” is a futile and inherently dishonest undertaking. This framework argues that no one knows why stocks do anything and essentially says all asset price moves are noise and should be treated as such. (This is not true and also not what EMH says.)

Back in the summer of 2015 — just before everything changed — there was a debate about what this take really meant. And then at some point the idea that no one knows anything became the idea that everyone knows everything.

This idea of a collective omnipotence goes beyond stocks and tracks for most any piece of Googleable knowledge. The internet makes trivia-style facts completely commoditized (which is why I think Jeopardy is having such a moment right now: it’s good to know there are some people who know a ton of shit without Googling). This might be bad and frustrating and seem to take some of the mystery out of being alive. But the internet also allows anyone to become an expert on just about any topic if they really put their back into it.

Spend any time on a reddit thread or a message board and in about four seconds you’ll see someone trashing someone else’s idea on the basis that their opponent obviously knows nothing about X. As always, the internet enables maximal interpretations of any idea to be proven both true and false: no one knows anything and everyone knows everything.[1]

This week, a small corner of the Finance Twitter circle I follow did a whole thing about newsletters. Why are there so many? Who would pay for this? How much? And so on. (Someone even started a newsletter as a joke after shitting on them in a tweet.)

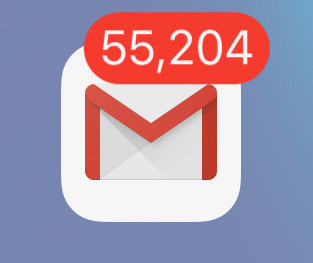

It seems that in the new year, everyone has a newsletter or is starting one. But the real question underwriting this debate is why the most archaic piece of internet technology we all still use — the inbox — is deemed a relevant place to explore as a business opportunity. Especially if we all know that no one wants to get more emails.

Dan Frommer — publisher of The New Consumer — wrote late last year that while newsletters might be having a moment, “If anything, it feels like The New York Times and Bloomberg further consolidated talent this year. Ambitious, in-demand writers and editors still mostly seem to want to play it safe, with lucrative opportunities and ample prestige available at big, legacy publications and comfortably LaCroixed digital shops like Medium.”

“I wouldn’t say we’re nearing a place where most of the top journalists and analysts go this solo, subscription newsletter route,” Frommer added. “But I believe in this model, and think it will be an important part of the future of publishing — and how many of the next generation of influential media brands will get their start.”

Byrne Hobart — who writes The Diff newsletter, among other things — argued this week on Medium that newsletter companies are actually real estate companies, effectively helping people create a digital version of the Midwestern neighborhood “where vague acquaintances you generally basically like are always going out of their way to say ‘Hi!’”

Byrne also notes that as the internet’s primary dissemination mechanism has moved from portals to RSS feeds to streams, what we’re essentially left with is television. As he puts it, “a bottomless well of content.” Newsletters are in-demand partly because they end.

This proliferation of newsletters is also specifically interesting for business media, because investing already has an illustrious (infamous?) history with the newsletter format. The Motley Fool has basically made an entire business out of newsletters. And individuals like Tim Sykes, Dennis Gartman, and Jim Grant have spent the bulk of their careers writing paid newsletters.

The retirement of Gartman alongside this newfound enthusiasm for the targeted newsletter isn’t, to my mind, a coincidence. What Gartman leaves behind is an incredible legacy of daily publishing of a product that spanned just about every asset class and offered readers an investable idea for each one. Even if Gartman was a great contra for many, his efforts to present readers with a call to action is an incredible feat to accomplish thousands and thousands of times.

But the Gartman Letter is also not a product that would succeed if started in 2020. The next (or rather, current) generation of investors has been raised in this know nothing/know everything paradigm. The only solid answer the average investor in 2020 will accept is: do whatever is cheapest. And so I don’t think you can create a consistent, reasonably well-received call to action on a daily basis in a world where refuting any one pillar of someone’s investment thesis is almost instantaneous.[2]

What I think you can do is offer something like a conclusion to the “bottomless pit” that fills our daily loggings on. And while my own inbox might suggest otherwise, there is a quantifiable endpoint to this mess of content that we know doesn’t exist on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, or Twitter. You can’t finish reading the internet, but you can finish reading your inbox. Even if you hardly read any emails at all.

And as the digital media industry has matured, completion is an idea that has been ignored and, by extension, undervalued. Digital media brands and their newsrooms have always been built around the idea that the river is endless. There is no point at which you can’t publish any more stories because the issue is closed and going to print. There is always digital real estate available on the site.

So for both publishers and consumers the inbox allows for a break from this rat race, a respite from the ever-growing traffic and content demands of editors and executives and investors. Finding a small, targeted group of readers who choose to consume what I write is the reason I started this newsletter.

Most of my digital media peers have spent their whole careers reaching readers that were mostly accidental consumers of their content.

Accidents don’t make a business model; a few thousand subscribers paying a hundred bucks a year might. Just as long as you’re not telling those subs what to do.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This. If you liked what you read, share it with a friend and make sure to subscribe.

If you agree, disagree, or just want to weigh in on today’s newsletter, reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland.

Footnotes:

[1] This form of internet-specific argumentation about relevance, expertise, and who has the right authority to tell me something is probably an overlooked part of the news business’ decline. Human interest stories still work because they don’t require anyone to know anything beyond: this is a person, stuff happened to them. Local news struggles in this new paradigm because consumers who spend most of their lives now connected to online reality rather than out-my-window reality don’t know why they should care about the haggling over a spending bill, the town vs. county tension over who is repaving Main Street, and so on. And forget about columnists: opinion pieces are now just one tiny part of an extremely dense ocean of people with the ability to broadcast takes.

[2] Though I imagine betting on penny stocks in an effort to get rich quick will never go away. This American need to make easy money while actually being taken advantage of by sharks is why daily fantasy sports has grown so quickly.