The Unicorn Decade is over and everyone is a winner

Airbnb and DoorDash were the exclamation point on a decade in financial markets that managed to prove everyone right.

Welcome back to I’m Late to This, a newsletter about things I’ve tried to not forget about.

If you found this letter through Twitter or other channels, make sure to sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish most Sundays.

And now, the end of an era.

Last year there was a bit of a cycle around whether decades end with the round number year or begin with them.

The events of 2020 have settled the debate. At least for this decade’s transition — 2020 is the year that ends a strange and chaotic decade, bringing so many of its themes to a logical endpoint.

Next year, the new decade begins.

In business and finance, the rise of the unicorn was a defining feature of the decade now wrapping up. The ubiquity of venture-backed businesses with valuations north of $1 billion created a new, lasting innovation in how investors, entrepreneurs, and consumers think about starting a company. The 2010s were the Unicorn Decade.

And this financing trend will endure just as more efficient food delivery, more available taxis, and more contingent work will change the economy in the new decade. Managing to finance operations for a company worth tens of billions of dollars while keeping that company private was and remains a novel solution for startups and their preferred investors.

There are, of course, many hundreds of companies worth many billions of dollars that remain private and always have been.

But the model for financing high-growth, “high-tech” companies was to give these companies a little bit of money, encourage them to lose all of that money while growing sales, and then go public. The unicorn era created several more cycles of raising and losing money to grow sales or market share and build a company’s mythology before public investors could get involved. Naturally, there are now a bunch of companies focused on getting more investors more involved in these earlier stages of raising and losing money.

Last week, as I’m sure most readers are aware, both Airbnb and DoorDash went public. These were the final two pieces of the consumer-centered venture boom that defined the Unicorn Decade.

Airbnb and DoorDash are now worth $83 billion and $55 billion, respectively. So Airbnb is the same size as Goldman Sachs and DoorDash is worth as much as Progressive.

And as happens when big IPOs come to market, this week’s events got everyone all worked up. But in the end, I think everyone gets to go home happy.

In consultant-speak, the IPOs of Airbnb, DoorDash, and the many venture-backed unicorns that came public before them turned out to be a win-win-win. If the Unicorn Decade party is now over, everyone who attended believes they had a good time.

Because every story that emerged during this era has resolved with that story’s evangelists feeling mostly right. So we all now move into the 2020s emboldened in thinking our respective visions for the future of capital markets are the correct ones.

The simplest critique of the last decade is that all this unicorn excitement merely amounted to a tech bubble 2.0. No one holding this view would see the developments of the last couple quarters as anything but a confirmation of their priors. “But they don’t make any money,” has always been a complaint lacking a significant amount of substance but is no less wrong today than it’s ever been. Airbnb and DoorDash indeed do not make any money. Not even bespoke-adjusted EBITDA money.

Meanwhile, those who always believed these businesses were creating a roadmap for the future of commerce, social interaction, travel, and so on view the market’s response to these businesses as confirmation that their view has been correct all along.

Another principal worry in the 2010s was the idea that financial markets had become too short-term oriented. In 2016, Hillary Clinton’s economic policies involved, in part, criticizing what she called “quarterly capitalism” during the presidential campaign. There’s even an entire stock exchange — the Long-Term Stock Exchange — that explicitly courts investors with a time horizon allegedly incompatible with public markets as structured today. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink also criticizes his executive peers along these lines each year.

And yet the way investors received not only this week’s new issues, but the debuts of stocks like Zoom (which saw shares double in 2019 before the pandemic-related 🚀) and Beyond Meat and Peloton and Pinterest show a clear desire to reward long-term visions in a way that runs counter to the myth of “quarterly capitalism” and make or break quarters.

If we look outside of new issues, the market’s ability to respect and reward a long-term vision can be easily seen in the performance of Disney this year. Investors are willing to back the generational transformation of a blue-chip business even when that transition is explicitly forecasted to result in lower near-term profits.

And sure, stocks still go up and down 10% (or more) after quarterly earnings reports. These one-off moves are often the target of criticism towards around a perceived short-termism among public market investors. But I’ve always found it an odd suggestion that one-day reactions to quarterly reports are nonsensical when said report is an all-at-once release of a huge trove of information about a business’ health. It’d be strange if the market didn’t care about material public information.

And so but the performance of Airbnb and DoorDash and Disney and Uber and Tesla are each, in their own way, a perfect illustration of how those on either side of the debate about whether markets are working walk away feeling like they are correct.

Those who think the market has gone mad and no longer cares about earnings will be dismayed by the performance of these stocks. Clearly, this view holds, the rallies in these stocks show the market has “detached from reality.” And this detachment — or worse, irrationality! — continues.

But those who believe the public markets are the ideal venue for accommodating and supporting long-term corporate visions will view these stock moves as affirmation of as much. Where else could DoorDash trade at a value 3 times that of Domino’s even though the business of the latter is clearly and demonstrably stronger today but might not be forever? The answer, of course, is nowhere.

So both parties move towards the next decade anticipating more confirmation of their world view’s rightness.

The manner in which this week’s stars — and many before them — went public also leaves everyone feeling like they’ve been right all along.

The IPO supporters see the process working as the initial public offering of both DoorDash and Airbnb valued the businesses at significantly higher levels than their most recent private fundraise. And by initial public offering we mean the actual offering, not the post-trading valuation. DoorDash was valued at $39 billion and Airbnb at $47 billion in their IPO, both significant premiums to their latest reported valuations in private markets. It seems the institutional clients of Wall Street banks do like money-losing food delivery services after all!

The direct listing adherents, meanwhile see first-day doublings as more evidence that the process continues to enrich bankers at the expense of the companies bankers are supposedly working for. IPOs, in other words, remain broken and crooked and should be abandoned so companies don’t give away money to bankers for reasons that benefit only the bankers. Affirm and Roblox delaying their debuts bolsters this view.[1]

Those who support or loath any of the above positions are likely displeased by this overview. Things have not been considered, caveats strategically left out or overlooked, my own agenda seeping through the lazy analysis, etc. etc. Substack exists so you can air your own grievances in peace and quiet while I go ahead and air mine.

But that I found myself embroiled in a chaotic series of Twitter threads about IPOs and direct listings on Friday merely cemented my sense from earlier in the week that the market debuts of DoorDash and Airbnb do indeed mark this era’s conclusion.

Because if we find ourselves in heated arguments over how a company comes to market then we acknowledge the debate has become aesthetic rather than practical.

In other words, it is no longer at issue that the businesses being brought to market are good, that the public market is a worthy final destination for an innovative venture-backed startup, and that public markets are capable of appropriately appreciating the long-term value of these businesses. All of which were at issue at times during the Unicorn Decade.

This disagreement over direct listing and IPOs is akin to debates over whether spread-concept offenses in football are the way a sport built on violent collisions and close-quarter combat “should” be played. That football is a good and worthy sport is not at issue; the disagreement lies in whether there is a right or wrong way to compete.

Ranjan Roy called all of these cross-currents at the end of this tech era “Exasperated Exuberance” in The Margins on Friday, writing:

For the old hats, is this what 1999 felt like, or was there more excitement at the time? Is it just the backdrop of COVID that’s muted the widespread joy of wealth accumulation?

As someone who takes a few hours out of their week to prognosticate on things in a newsletter, I try to have a viewpoint. I can genuinely say, this is the first time in a long time, where the mania has hit such a point, that I am genuinely lost as to what might happen next. The dynamics driving this bubble are not set to change at any time in the near future.

And, yes, I mean no one knows what might happen next. But the exasperation that Ranjan feels about All Of The Things can, I think, be explained by the dynamics outlined above.

All of the major players, the major themes, the major fights of the cycle just-completed ended up resolving with a return home to declare victory. No one except Adam Neumann and Travis Kalanick really lost anything this cycle and even then: they both still got rich.

Which suggests either things really have changed in markets forever or there is another shoe yet to drop. Though there is a third possibility which seems more likely, a possibility that fits with what it actually feels like to be alive today. Which is that there really is no universal truth to agree on anyway. If half the country won’t accept the results of a presidential election, why would a financial market cycle come and go with anything resembling definitive rights and wrongs?

If we thought that back in 2015 all of these fights about the future of markets would one day end with victors declared, then it’s now clear a world in which resolution is found so neatly no longer exists. The reason you can outline the case for every version of a Unicorn Decade argument being right is not that there’s no evidence to prove anyone wrong, but that any evidence which appears to do as much will simply be ignored.

People love quoting the not-actually-Keynes line that when the facts change they change their mind, but there’s no incentive to actually do this anymore. (Perhaps there never really was.) You can be wrong about what seem like basic facts in your field and still be a professor at MIT or a top analyst at a Wall Street bank.

There is no truth so potent that it would derail anyone’s efforts to declare some feature of a market, a community, or a political platform as their own definitive capital-T truth.

So we’re all always right and always wrong, all the time.

The only thing that changes is whether you want to be a winner or a loser. No one else will call it for you. And even if they did it wouldn’t matter.

Notes and errata

Why we all seem to care so much about what happens to a handful of consumer-facing apps is a worthy topic for an entirely separate newsletter. One I will not be writing this week.

But there’s an explanation I find compelling which had originally featured prominently in this week’s letter and that ultimately ended up homeless in the flow of the argument.

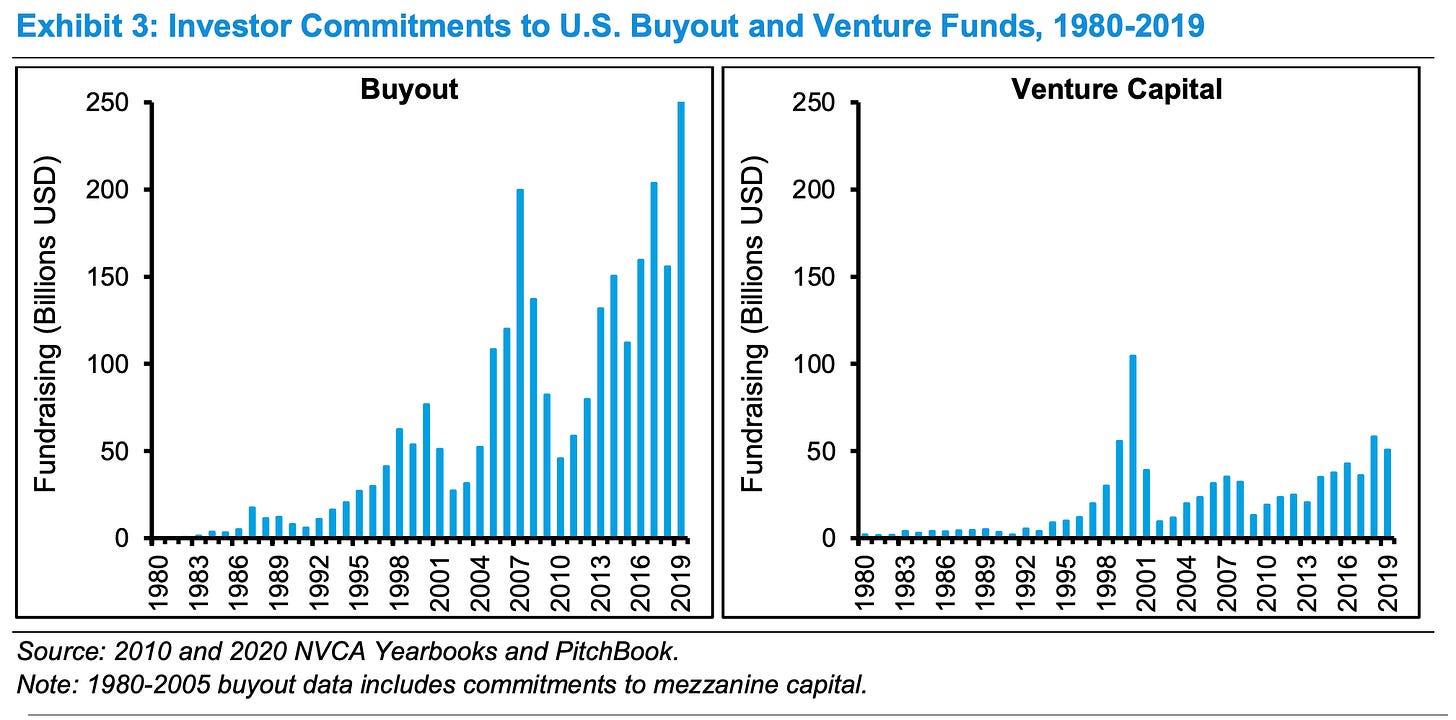

In a paper published in August that we’ve previously cited, Michael Mauboussin detailed the flows into venture funds. These flows are a lot less than you’d (I’d) think. Especially when compared to buyout funds, another alternative credit opportunity which has become so trendy for major institutions. Another topic for another newsletter we’re not writing today is the Swensenification of institutional portfolios. (I didn’t care for this headline from II, but this is a good story on the topic.)

Good storytelling, however, requires big highs and big lows and venture offers both.

Venture and buyout are investment styles which lend themselves nicely to the kinds of stories that people who just want to be entertained might like to hear and read about. Mauboussin writes that — “Because there is discretion in how private funds report their returns, some academics have argued that the risk is understated,” which moves that buyout bubble closer to the venture bubble on the chart below.

And in this chart and it’s easy to see why the media writes so much about the venture capital space — and why venture thinks it has such interesting tales to tell about itself — and why Barbarians at the Gate is one of the canonical business books.

So what all has gone on in markets this year has lots of truths, but the places from which commentators like me tend to seek those truths are the asset classes explicitly designed to create the kind of drama worth writing about.

For whatever that’s worth.

1: Though, the question for these companies and any other going public is, as ever — do you need to raise money? If the answer is yes, then you need to go public. You’re free to find bankers who will do it in a certain manner, but if your liquidity needs can only be fulfilled by the depth offered by U.S. public markets that is your one choice. If, however, you need to raise capital in the future but want to create liquidity for early investors, then a direct listing is a viable alternative. But you cannot pull an IPO that was needed for the reasons that IPOs are needed and replace the process with a direct listing: they are entirely different funding events because only one of them actually is.