Public markets are the new private markets

Why SPACs are really a play on the long-term visions public markets support better than private capital.

Hello and welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter from Myles Udland about stuff I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If you’re new here, thanks for signing up!

More than 1,600 readers get this letter sent to their inbox each Sunday. We hope to keep growing this community over time.

If someone sent this your way, or you found this post through Twitter or other channels, make sure to sign up below and share this post with a friend or colleague. I’m Late to This is free to read and plans to stay that way.

And now, markets.

Matt Levine has set a number of trends in the financial commentary space.

But none is more influential than his argument developed over the last half of the 2010s that private markets are the new public markets.

For me the idea has always been, basically, that in a prior business climate you had to tap public markets to get adequate funding for your big idea; in the 2010s, private capital pools accomplished those goals better.

There are several ways for investors and operators to play this theme.

The most popular asset class that seeks to separate itself from public markets in a philosophical way is venture capital.

Venture appreciates the promise of technology, can foster coherent visions of the future, makes the world a better place, and rejects the stock market holding on to the business models of the past. A derivative play out of this group saw the opening of a long-term stock exchange explicitly aimed at courting capital zagging towards a long-term view when public markets were seen as zigging towards the myopic demands of quarterly earnings. (I posted a brief thread on this endeavor last month for those who are interested which served as something like the seed for this letter.)

Then there is a PE-type investor that sees private capital as having the discipline to stick through a tough restructuring of a business the glare of public makrets wouldn’t be able to stomach.

All of these distinctions, of course, are crude and none of these are particularly new ideas. But the amount of capital allocated to PE and venture over the last few decades has enabled a wider swath of investors to pitch funds operating under these frameworks and so there is more talk about these investing approaches and thus the practices seem new and novel. There is also a Yale-influenced piece of this for institutions that is worthy of a separate newsletter we’ll table for a later date.

So but of course, 2020 being 2020 and all, we have now inverted this entire structure.

Public markets are now everything the private markets positioned themselves as being during the last decade. And are declaring this truth in the most rambunctious way possible.

And that way is through the SPAC.

SPAC Attack

SPACs are special purpose acquisition companies often described in the business press as “blank check vehicles.”

The basic outline is that instead of learning about a company, meeting with their founders or executives or something and then deciding whether to give them money, investors give money to other investors who will then go meet with companies, buy one outright, and take it public. More or less.

And, yes, the SPAC boom can seem kind of scammy and weird and gives us things like this.

You know, big building, big valuation.

And as ShitFund notes, SPACs are not an asset class. They are a comp scheme.

Which doesn’t really disqualify these vehicles, it is just worth being clear-eyed about what SPACs are and are not. They are alternative funding schemes that enable early investors and employees quick and ready access to more capital with which they can either grow the business or cash out.

But to an extent, I think the SPAC itself is tangential to the thesis the SPAC boom is unlocking right now. Or at least the thesis SPACs are gesturing towards while certain unsavory characters ride the wave.

And that thesis says public markets do a better job of appreciating long-term, big idea opportunities than private markets.

The types of investors — Jeff Ubben, Bill Ackman, Chamath Palihapitiya, among others — who are sponsoring these blank check vehicles are not stupid. In fact, they are the opposite of stupid. And while the above point on SPACs acting more as a comp scheme than an asset class is important, these sponsors are acting with conviction that public market investors will more efficiently and readily appreciate the value of what we’re bringing to market than the so-called “smart money” that made private markets the new public markets.

So, again, sure, the SPAC can be — but is not exclusively — a vehicle for some shitty ideas the same way all other asset classes can have their dogs: Juicero, Theranos, any PE-backed IPO, and so on. But the view right now is that on balance the public market will give companies and their sponsors a better valuation than private capital will.

Public markets, in other words, are the new private markets.

Everyone is an alt-kid now

This is, of course, where private capital inserts all of the arguments in favor of their investment in or ownership of a business. Operational experience and know-how, resources for bolt-on acquisitions, patient capital, infrequent marks to market, and so on.

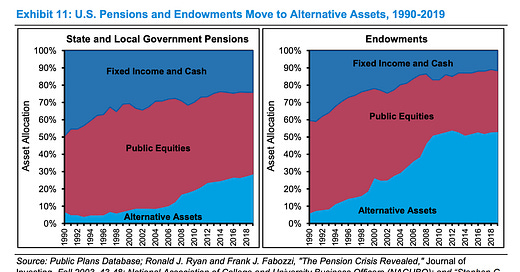

These are all fine arguments and investors (by which we mean institutions) have voted with their feet, as these charts from Michael Mauboussin’s latest paper outline.

Allocations to alternative assets, be it PE, real estate, or venture, have surged while institutional allocations to public equities have shrunk. So cry no tears for PE or VC.

But the way public markets have behaved during this pandemic — quickly pricing in an acceleration in growth during what has so-far been an above-consensus outcome for the kind of business listed on a public stock market exchange — refutes a lot of complaints from the 2010s about the market’s short-term focus.

Complaints which said quarterly earnings were stifling innovation, that shareholder primacy had sawed off the promise of free capital markets, that only through re-imagining the market’s relationship to businesses could future opportunities be realized. All of which, in hindsight, has some big “I can’t believe we’re still underperforming” energy.

We have now seen a few decades during which capital has flowed towards alternative investments — anything that isn’t a stock, a bond, or cash — and the most recent justifications for this allocation became accompanied by ever-grander visions of what this asset class could offer. It is not clear these visions are coming to pass.

And there is an example away from the SPAC or venture space that is most instructive in showing how public markets are the place — right now — for companies to get the most aggressive and favorable mark from investors willing to bet on a vision.

And that example is Penn National.

How to create billions of dollars of value in three quarters

Penn National is a racetrack and casino operator. In January the company acquired a stake in Barstool Sports that valued Barstool at ~$450 million. As Web Smith outlined in a post this week, when Penn took its stake in Barstool its market cap was $3.3 billion. Now, Penn’s market cap is $10 billion.

A few years back, The Chernin Group paid $12.5 million for a stake in Barstool, according to founder Dave Portnoy. Now, everyone is a lot richer. As Web writes, “With upside remaining (TCG still owns a stake in Barstool) and newly acquired stock in Penn Gaming — a publicly traded casino holding company — TCG created a unicorn asset out of a sports blog.”

And the way they created this unicorn is through the public market. Penn’s stock chart tells a simple story — investors think Barstool is worth several billion dollars. And this just nine months after the business was valued at $450 million.

As part of a publicly-traded vehicle, Barstool’s success can get a real-time mark from a broad range of investors. Investors that, contra popular narratives about public and private markets, are willing and able to bet on aggressive growth visions. Moreover, fans of the company are now able to invest in the business alongside the content and talent they love. A benefit that is Barstool-specific to some extent, but also outlines how public markets can better unlock value for businesses that have value to unlock. So long as this allegedly unlocked value doesn’t rely on esoteric financial engineering or involve explaining-away obviously terrible unit economics.

And sure, not every company has a public face who swings a green hammer on livestreams and says stocks only go up. But Penn/Barstool is not all that unique in having a fan-like devotion from an investor base that understands a corporate vision (rather than a strictly financial vision) and can profit alongside their passion.

Tesla is an obvious example here. Similar examples of passion for a brand or an executive driving returns over time include Costco, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, the Malone Complex. Peloton has certainly fit this bill in 2020. And I’m sure the #CompounderBros from FinTwit have dozens of other examples that fit this basic framework.

And, like, what is the outperformance of so many B2B SaaS plays if not public markets understanding how the future of the enterprise will be shaped, which companies will be the winners, and assigning multiples accordingly? And yes, basically all of these businesses took some form of venture capital that produced a huge return for early investors. But the performance of these names suggests public markets shouldn’t be seen as a dumping ground for already-mature businesses. Instead, the public market today is where your vision goes to flourish.

Now, relative to a lot of other things I’ve written in this space over the last ten months, this piece probably has the highest risk of looking completely asinine, like a “sentiment top,” or something similarly embarrassing in short order. Public markets right now are very excited about a lot of things and, well, there are a few things going on in the world right now that could change this sentiment!

But the more I thought about this piece, the more a brief reflection on the last decade helped focus the idea that we were really staring the best value-creator and returns-generator — the public equity market — in the face all along.

Unicorns really did change everything

Reading through some of Matt Levine’s Money Stuff newsletters from 2014/15 in drafting this piece, I found the origins of his “private markets are the new public markets” idea starting to take shape in the spring of 2015. Specifically, in his April 14, 2015 newsletter.

This post bounced off Larry Fink’s memo to executives that spring which criticized the primacy of creating shareholder value above all else. (Sadly, all the links in and to Matt’s old pieces are dead on Bloomberg.)

A few weeks ago I described my simple dumb model of corporate finance, in which mature companies mostly can’t coherently create value over the long term, and so give the money back to investors, whose job it is to find the next company that will create value over the next short term. This makes the investors’ job harder, since they have to do the job of capital allocation rather than leaving it to corporate planning departments. It’s much easier to hand your money to a good permanently growing company and let it invest wisely than it is to constantly find new projects to fund... My simple dumb model also involved investors taking the money that public companies pay out in dividends and buybacks and investing it in private companies, which is where the long-term value-creation plans live these days.

Pretty much all of the companies touted five years ago as disruptors possessing the kind of vision public companies can’t execute on, of course, are now public. (And the only industry with consistent innovation anyway is Big Food.)

Which doesn’t necessarily negate the idea that private markets are where long-term value creation plans live, but does suggest the public markets offer something that private markets cannot. The simple answer to what that something is is probably just: capital. And that might be the entire case to refute this take. Maybe the public markets really are as bad as the detractors say and their only advantage is offering companies a deeper pool of capital. Except that the pitch for private investors over the last decade has been access to capital in addition to all the other visionary stuff? This could go on.

So but then in a May 11, 2015 follow-up which includes this incredible quote from Slack founder Stewart Butterfield — “This is the best time to raise money ever...It might be the best time for any kind of business, in any industry, to raise money for all of history, like since the time of the ancient Egyptians.” — Matt adds:

Honestly it would be odd if the ancient Egyptians had a larger venture capital industry than modern Silicon Valley. ("I just invested 20 million shekels in a new on-demand irrigation startup at a billion-shekel valuation." "Oh we call that a 'sphinx.'") The comparison that springs more readily to mind is the late-90s tech bubble, when it was really easy for dumb tech companies to raise a lot of money in public markets. Pets.com is the notorious poster child/sock puppet for that bubble, and it raised $82 million in its initial public offering, just a wee fraction of what Uber gets every time it so much as glances at the private fundraising markets.

You could have a model here where public markets are diverse and transparent (short-sellers short, value investors stay away from overpriced companies, analysts criticize disappointing earnings), while venture capital is a clubby business driven to groupthink by its specialization (if your job is investing in tech startups, you'd better keep investing in tech startups!) and a desire not to miss out on the deals that everyone else is doing. This model strikes me as overstated — part of why private valuations are so high is that a lot of the money is coming from erstwhile public-company investors rather than traditional venture capitalists — but nonetheless useful.

I know his archives have dozens (hundreds?) of early examples like this, and eventually the newsletter got a recurring section sub-headed: Private markets are the new public markets.[1]

An undercurrent in these early commentaries on the primacy of private markets is the business investors were most interested in at the time and firehosed just an unbelievable amount of money towards — Uber.[2]

In his 2015 executive letter, Fink complains that companies are not doing enough capex and R&D to help discover the future of our economy or whatever. Uber was and is a great solution to that problem! The company’s business requires an almost unlimited amount of capital to acquire both customers and suppliers and facilitates these transactions at a loss.

Now, as Modest Proposal said on Invest like the Best last week, Uber is one of those businesses that if you live in a city like NY or SF, you immediately understand as the greatest thing ever. And indeed, I once made the case that Uber is the company that unlocks the potential of our smartphones better than any other business. The company also exploited labor laws and fostered a culture of sexual harassment that undid its founding executive group and allowed Lyft to make market share gains in the U.S. Uber is everything this last cycle brought us all in one exaggerated package. They also say that adjusted EBITA profitability is coming soon!

But a major part of that cycle Uber defined in was also rife with investors willing to throw money at capital intensive consumer products in the hope of attaining monopoly-level market share.

And all this money-throwing created very high valuations. The unicorn was and remains a real innovation in financing. Unicorns offer truly novel solutions for the investor community always in search of excess returns. They accept lots of capital, they offer higher valuations for that capital, and they pursue the kinds of moats that attempt to appeal to a certain sensibility among post-Buffett investment managers.

Junk bonds, LBOs, dot-com stocks, CDOs, CAC black hole software-enabled businesses are all of a piece, channeling the energy of investors towards a real but narrow opportunity. SPACs may well be the next in line.

But the SPAC trend also gestures towards a rejection of the latest en vogue idea for late capitalists. The idea that public markets cannot see what those who operate under more secrecy with fewer disclosures can.

So in a roundabout way, SPACs support another view many of our most influential thought leaders of the last two decades have advanced — the idea that offering more of everything to everyone will surface the best solution to all problems.

And we find more of everything and everyone in the public markets.

1: And for those reading who are Levine-junkies — which I assume is many if not most readers — these early outlines date to the era when “People are worried about bond market liquidity” was the most popular bit at the time.

2: It makes sense why WeWork later became the most-covered company in Money Stuff — it was the company that finally asked eager investors if they had perhaps gotten too excited about private companies.