Stocks trade at prices

Why markets tell us to live in the world as it is, not as we think it should be.

Hello and welcome back to I’m Late to This.

We haven’t published since November 8 and the absence was unplanned.

A full newsletter was drafted for each of the last two Sundays and the publish button was never pushed. The reason is that I simply wasn’t all that interested in what I’d written. So why would anyone else be?

This weekend marks the 53 week anniversary of starting this newsletter and a lot has changed since then. I still think a weekly publishing schedule is best and I hope to stick with this going forward. Structure unlocks creativity and I’m wary of allowing my inherent laziness to gain greater control of this process.

On the other hand, the intimacy of a newsletter sent directly to a reader’s inbox assumes a certain level of care about what has been published and this tacit agreement is one I hope to never violate. Though I suppose everyone who has unsubscribed, stopped opening this email, or been dissatisfied with any of the 47 prior issues of this letter perhaps feels I already have.

As always, if you found this letter through Twitter or other platforms and like what you read, make sure to sign up below so you never miss an issue. We aim to publish each Sunday.

And now, scattered thoughts about life and markets.

A theme of this newsletter is that we live in the world as it is.

There is no way that things should be, but simply a way things are.

As venture capitalist Chetan Puttagunta once said, his job as an investor is to see the present very clearly.

I think this is the best any of us can really strive for.

So often in finance, economics, and life, however, our teaching leads us towards the idea that there is in fact a baseline from which things deviate. That there is a zero-sumness to human existence, that all things eventually even out, and that it is in the zigs and zags from a kind of steady state reading of history that interesting things happen — pandemics, wars, social unrest, surprising election results, stocks going up a lot.

The zigs and zags are also where we’re told all the money is made.

But a strong determinism has taught me to avoid seeking truths in the world much beyond the bounds of the cliché which tells us things are what they are. There’s an ontological literalism embedded in this framework that is soothing.

Why think any harder about the world when it’s all just right in front of you? Like all value sets, of course, this view has its limitations. But I find that it at least serves as a good governor on one’s belief they might be smarter than anyone else.

So but I’ve been thinking about this tension between what is and what should be because of what else — the stock market.

Stock prices are at record highs. Lots of people are perplexed by this. Perhaps even upset about it. But instead I choose to accept that the level of stocks is the level of stocks. And really, as the title of this post posits, all stock prices can ever really be are stock prices. Nothing more, nothing less.

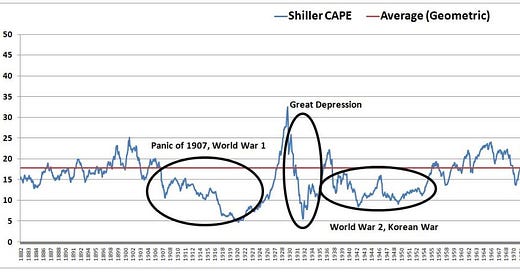

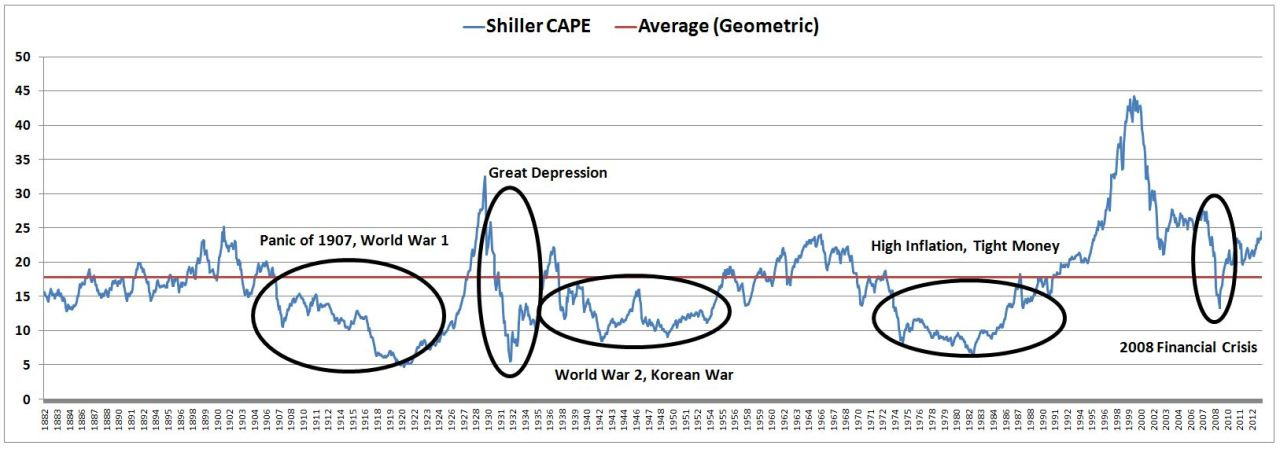

The Jelly Donut pod recently resurfaced an old Jesse Livermore piece from 2013 about valuations. If you read this piece and understood the conclusions Jesse was driving at you would have made a lot of money.

The central contention is that while historical measures of the stock market make (or made) stocks appear expensive and thus warrants caution, the measures that shape this history are themselves flawed. And by exploring these old ideas we learn what shapes the present and can see stock prices for what they are, not what they should be.

But a worldview which pays outsized respect to the existence of a correct or stable version of the past from which our present follows prevents this outline from coming into focus. Jesse writes:

There is no external, divinely-imposed valuation level that the stock market has to take on. Rather, the stock market takes on whatever valuation level achieves the required equilibrium between those that want to get in it, and those that want to get out of it. At all times, every investor that wants to get in the market needs to connect with an investor that wants to get out of it. If there are too many that want to get in, and not enough that want to get out, the price will rise until the imbalance is relieved. If there are too many that went to get out, and not enough that want to get in, the price will fall until the same. The process is reflexive — investors want to get in or out based on where the price is and what it is doing, but they also make the price be where it is and do what it is doing, through their efforts.

When I entered the financial media in 2012, I did not realize I was entering the financial media. All I knew is that stocks were involved in the job.

So I read some books and the Wall Street Journal and ZeroHedge and it seemed that all of the experts I was supposed to be listening to thought the stock market was going up too quickly. Or that the whole thing was a bubble, ready to crack, unjustly defying the laws of economic nature.

Just a few months into my first job the market made its first new high since the crisis. Since 2013, the S&P 500 has more than doubled. And hardly anything has changed in how most pundits see the stock market — expensive relative to history and setting up investors for some dangerous future plunge.

But in 2018 and 2020, stocks actually did fall quite a bit and quickly. Why stocks fell for a time in these years, however, is quite explicable. And had little to do with the calls we’d all be hearing for years. Interest rates were raised faster than warranted by economic prospects in 2018 and a global pandemic in 2020 made holding long-term assets quite challenging for a time.

And yet so many ongoing calls for lower stock prices center around a framework which argues that there is a historical norm for the value of shares in large businesses. That stocks are supposed to be worth a value that isn’t random but True. That it is only natural for interest rates to be at certain levels. And yet when stocks actually fell the cause wasn’t anything that wasn’t happening right out in front of investors paying attention.

The beauty of giving oneself over to the stock market’s logic is that all the easy things get figured out for free. Want to know if a company is doing well or doing poorly or doing just fine? Look at the stock. How is the economy doing? Look at all the stocks. If anything, we ought to take even more signal from market prices than is commonly done today.

And this is not a “skin in the game” Talebian jab against people who aren’t invested or haven’t had their brains broken by markets like me. I am simply arguing that aggregations of pricing information will be more correct about the value of any asset than one individual’s view of said asset.

The spread around the edges of this truth, of course, is where profits often exist. And I’m sure people will keep trying to find these. There are industries and business lines where serving as an arbitrageur makes sense and may indeed be the only way to exist. Arbitrage is not a thing that doesn’t exist. But it also isn’t the only thing that exists. And more often than not these opportunities mislead.

Because believing that there is some pure uncut truth which sits below or beside the random chance that comprises the real world leaves you thinking that only the shortcomings of others offer a path to success.

And yet in the end we’re all in this together. And things are better when stocks go up.