This argument is always wrong

Saying that something will eventually matter doesn’t mean it does or will, now or ever.

Hello and welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter from Myles Udland about stuff I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If you’re new here, thanks for signing up!

If you’re not, your continued readership is greatly appreciated.

If someone sent this your way or you found this post through Twitter or other channels, make sure to sign up below. We publish every Sunday.

If you like what you see here, please share this post far and wide.

Today’s post marks the 35th edition of this newsletter since launching last November. Over 1,250 people receive this email every week, and I hope this community continues growing for years to come.

And now, onto this week’s letter about an argument that is always wrong.

There are lots of different ways to be wrong on the internet. There are many ways to be wrong in real life. And there’s one argument used widely in both settings that is always wrong.

“It might be fine right now, but eventually this will be a problem.”

I’ve been kicking around this idea for a while. The elevator pitch is: anyone who tells you something that isn’t a problem right now will be a problem someday is merely holding themselves out as smarter than you, won’t consider evidence they are wrong, and doesn’t really care.

This argument comes from a secure position. The consequences — were they to materialize — would be someone else’s anyway.

And then, right on cue, on Friday afternoon Fitch dumped a textbook example of this concern trolling about some current non-issue that poses a serious yet vague future risk.

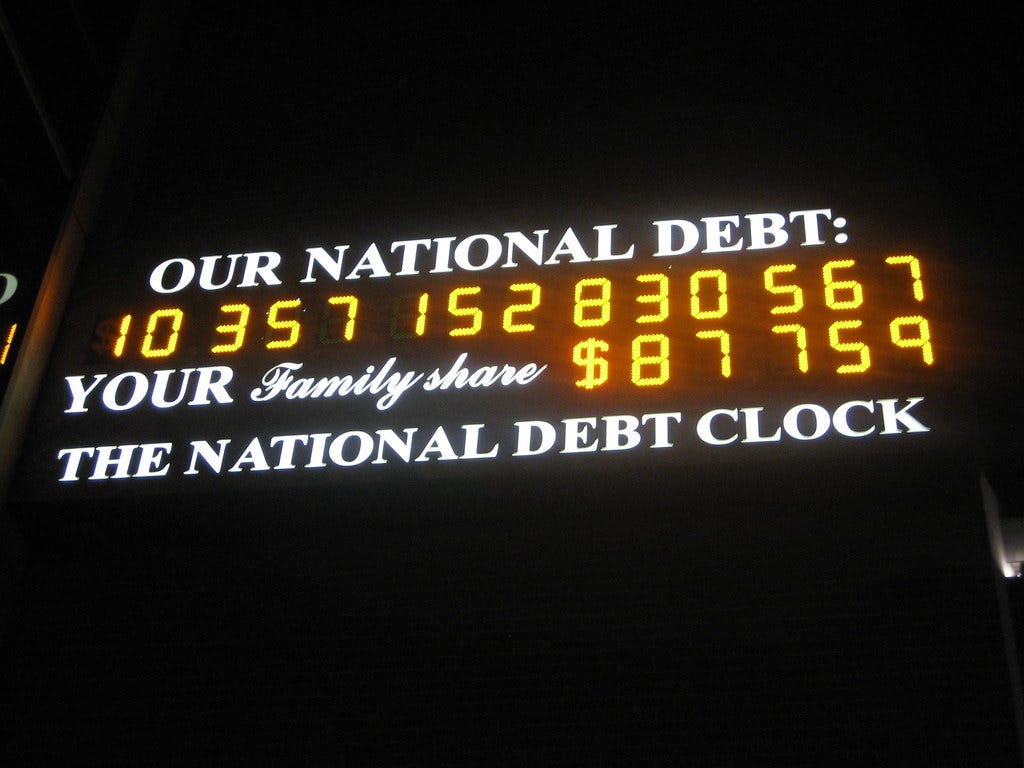

And that is the deficit.

In politics, economics, and Serious People circles, this concern is the canonical “eventually it will matter” topic of discussion. No take fits this template more tightly than concerns over the national debt and the U.S. government’s persistent budget deficit.

Here’s otherwise capable Fed chair Jerome Powell speaking on the topic just a few months back:

In terms of fiscal concern…I have longtime been an advocate for the need for the United States to return to a sustainable path from a fiscal perspective at the federal level. We have not been on such a path for some time, which means — just means that the debt is growing faster than the economy. This is not the time to act on those concerns. This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to — to do what we can to support the economy and try to get through this with as little damage to the longer-run productive capacity of the economy as possible.

The time will come again — and reasonably soon, I think — where we can — where we can think about a long-term way to get our fiscal house in order. And we absolutely need to do that. But this is not the time to be — in my personal view, this is not the time to — to let that concern, which is a very serious concern, but — to let that get in the way of us winning this battle, really.

And so, naturally, Fitch downgraded the outlook for the U.S. government’s long-term financial position to negative because of, well, stuff that will (could!) eventually be a problem. Powell opened the door. Fitch just walked in.[1]

“[The] Outlook has been revised to Negative to reflect the ongoing deterioration in the U.S. public finances and the absence of a credible fiscal consolidation plan,” the firm wrote in a piece on Friday that advances an argument hinging explicitly on a this-might-someday-matter framework.

The kind of framework that is at once unprovable in the affirmative but also seems not disprovable in the negative. (Even though it is.)

I will exercise restraint in discussing Fitch’s decision, but it is a statement filled with vague suggestions about potential scenarios for the government’s financial accounts that could be worrying but are presented as sure conclusions if Something Is Not Done.

And that Something, of course, is austerity. Fitch is worried about an imagined future in which runaway inflation threatens the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency and thus makes borrowing so prohibitively expensive for the U.S. government that austerity is forced upon the state by markets. The workaround, then, is to enforce austerity now.

But actual — not imagined — evidence in no way supports this view. (Again, these arguments cannot be proven in the affirmative but they can be disproven in the negative.)

On Friday, the 10-year Treasury yield closed at a monthly record low of 53 basis points. What financial markets are telling everyone, and most importantly the U.S. government, is that investors have almost no concerns about the government’s ability to pay back their debts. In fact, this yield suggests that, if anything, investors are clamoring for even more debt to purchase from the U.S. government. If markets were concerned about the deficit, borrowing costs for the government wouldn’t be at record lows.

And, yes, sure, there are objections that Treasury yields aren’t only reflecting a soundness of financial position because with the Federal Reserve engaging in huge purchases of Treasuries while pegging its benchmark interest rate at 0% it follows that interest rates (and thus bond yields) across markets of all types will fall. Additionally, market participants assuming relative austerity and restraint from the U.S. government — and, in turn, slow growth — in the coming years could be supporting low yields. The concerns raised by Fitch and others about the state of the government’s finances are so grave, however, that to claim technical portfolio-construction factors are adequate to explain the demand for Treasuries is preposterous.

And so instead of recommending that the issuer of the world’s reserve currency do everything in its power to sustain the present quality of life for its citizens amid the country’s darkest economic moment since the Great Depression, Fitch thinks the U.S. government should impoverish more than the millions already being explicitly disenfranchised by government policies because… the future might be uncertain.

But, again, I do not want to dwell on this specific view any more than I already have. Fitch has served its purpose.

Adherents to this line of thinking believe they are the only ones being sober, rational, and responsible. But the problem with the structure of this view is that it is, at its core, a political argument first and last.

And I don’t mean political in terms of it being, like, a Right or Left take or whatever. But political in that the argument is prescriptive, not diagnostic. The view that “eventually, this will be a problem” reveals the gestured-towards “problem” not as the likely or logical outcome that follows from present trends, but as the preferred destination of those advancing the argument. Suggesting that one day some perceived imbalance in the present state of an organization, government, trend, culture, rival, etc., will necessarily cause a problem in the future merely outlines a desired equilibrium for said entity.

To go back to Fitch’s outline for its perceived problems facing the U.S. government, the entire piece really says nothing beyond “Fitch wants the government to balance its budget.” Now, why Fitch or anyone else wants that is an interesting line of inquiry. Stephanie Kelton compellingly outlines in The Deficit Myth that the foundational misunderstanding of government finances is that the government ought to follow the same basic rules as businesses and households. You know, the rules we have to follow, like paying back our debts. But that is not the world we live in. Our government issues the world’s reserve currency; we as regular citizens and businesses as corporate citizens do not. Kelton’s argument is descriptive; Fitch’s argument is prescriptive.

And this misunderstanding between what is and what should be is why these arguments are always wrong.

Suggesting that something will be a problem at some vague future point also allows you an out when forced to grapple with questions about why the world looks the way it does. This argument skirts any responsibility to explain the premise from which your conclusion follows. Which couldn’t happen anyway — the premise is: “I think this is true.” And this inability to see and describe the world as it actually operates is why those who take action along these future worry lines of argument will be forced to fold well before things break their way (and if they ever do, it’ll be by accident anyway).

In the investing world, we see this play out through several lenses, the most useful of which is that provided by the valuation worrywarts. If anyone betting on bank and energy stocks while shorting FAANG is reading this, they will be immediately pissed. So it goes.

But think about what’s happened in markets over the last decade and been exaggerated in the last six months. Investors have, on balance, rewarded companies that are growing quickly rather than companies that are reasonably valued.

Which is not to say that some companies don’t fit into both buckets. There is Apple, for instance. But an adherence to a framework that suggests the present value of a company’s future cash flows must fall within some sort of historically normalized range has kept many an investor out of names like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Tesla, Shopify, and so on.

As Patrick O'Shaughnessy said to Charlie Songhurst on a recent episode of his podcast:

Everything you highlight suggests exactly what's happened in the last 10 years, which is that the primary sin for public market investors is being overly quantitative. That basically anything quantitative, whether pure quantitative strategies or people that rely heavily on spreadsheets, as you say, have tended to get trounced by people that have the more qualitative, fundamental insight about what will become a very big market.

To use overly broad generalizations, the spreadsheet approach that Patrick outlines is a solution in search of a reality for a preferred equilibrium in which businesses are “reasonably” valued based on expected future cash flows. And I put “reasonably” in quotes because, well, that really is the linchpin for this entire argument.

An argument that says, for instance, that someday Netflix’s valuation or Facebook’s regulatory overhang will “matter,” aka make the stock trade lower to a more modest valuation.[2] So while many securities may indeed trade towards what seems like a naturally selected multiple of a company’s earnings (a golden ratio, as it were), that this will hold across all scenarios or prevail in any future market environment is equally as speculative as Tesla longs are deemed to be.

And, yes, I am aware that it is my decision to hinge this view on a weak adverb like “reasonably.” On the other hand, the broadest Buffettism you’ll hear any new value convert say is something like — “I want to buy a great business at a reasonable price.” And so.

The suggestion I’m making, however, isn’t that you should just go buy all these stocks to wash away the sins of using a dated valuation metric. I mean, you can do whatever you want. Anyone that has been reading this newsletter or any of my other work for years will be well aware that nothing I say is investment advice. Like everyone else, I’m just winging it here.

The point is just that the case for any non-issue today mattering in the future hinges, really, on you being smarter than everyone else. On you possessing some grasp of a future risk no one else has thought about and that is being collectively ignored by choice, instead of already factored into the real world we live in. Which leaves those making arguments towards some future worry wrong in either direction — you’re either projecting some imagined discipline on the future or misunderstanding the present.

And the solution here is simple: we must pay more attention to the present and stop imagining the future.

It is only through willful delusion that so many choose to worry about un-real futures, about stylized spreadsheets that claim programs like Medicare and Social Security are going to be bankrupt, that claim the government must tighten its belt to fend off the bond vigilantes, that claim what you see with your own eyes right here, right now, is the lie.

As I wrote a few weeks back, at the five month mark of this crisis, it is more valuable to take stock of what we know than to continue focusing on what we don’t. The clues for how to proceed from here are right in front of our faces.

What we know about the virus, about what responses to our health and economic crisis work, and about which don’t, are the kinds of things we need to be focused on. Because there is a real world of choices and consequences and we live in it.

Focusing instead on unknowns of the virus, of the future, of our national fortitude to do what is right is what leads states down the road towards a surge in cases, leads baseball down its disastrous start to a season, is what seems to be leading football towards the same. Unknowns enable magical thinking and everyday there are fewer of these outstanding.

It’s one thing if you’re an investor who underperforms the market for years on end because you’re waiting for stocks to get cheaper. You’ve cost yourself and investors money, but it’s only money.

But it is another thing if you’re a lawmaker stripping away safety net protections from those you don’t like because you claim All Of This is going to be a problem. People are dying because of worries about a future the CBO’s projections spit out in Excel, because of an inability to tell the country to wear a mask and stay home.

“It might be fine right now, but eventually this will be a problem.”

This argument is gaslighting.

The stakes to exposing those who follow this line of argument are high.

Because this imagination is what holds back our present.

Because these imagined futures will never come to fruition.

Because this argument is always wrong.

[1]: And, yes, Powell said that now is not the time to act on this concern and in so doing affirms what needed to be done yesterday by Congress — an extension of emergency unemployment benefits, another rounds of $1,200 checks, eviction relief, and business loans (ideally, grants). But he is still running this argument through a standard deficit scold loop wherein whatever is being done now is excessive, whatever is done in the future must be restrictive, and the evidence for why there is some reckoning point in the government’s financial future remains “a feeling.”

[2]: This also opens up the whole “what has the market priced in” reductio line of thinking which I find interesting but will relegate to a footnote. My house view is that the market has always priced in everything. So arguing that Facebook’s regulatory issues, for instance, aren’t priced into the stock right now suggests that the market isn’t efficient. And while perfect efficiency is not an accurate way to describe financial markets, almost perfect is close. Suggesting that a stock which has dozens, hundreds, perhaps thousands of sophisticated investors following the company’s every move hasn’t been priced to reflect the collectively-perceived risk of, say, a breakup is to hold oneself out as all-knowing in a way you certainly are not. Regulatory challenges, in other words, have absolutely been contemplated by Facebook’s current shareholders. They’ve been contemplated by every company’s current shareholders! A better way for understanding markets and businesses than building a model is cutting one down — assume everyone already knows everything there is to know about a company and work backwards.

Myles, thanks for your nice article. Please allow me to disagree with you though. Theoretically, the market is supposed to be efficient; however, human beings are intrinsically emotional, irrational and biased. It’s very likely that some ‘weirder’ or ‘crazy people’ or ‘party pooper’ turn out to be right. Those who claim that the market is overvalued, or that governments won’t be able to service the debt are supposed to be right according to classical analysis; but they underestimate the role central banks and governments play, and the effects of USD hegemony. At this point, investors are clamoring for treasuries, but what if the debt keeps growing at a rapid pace? MMT does claim that government debt is different from private debt, but it could not be issued to the point of hyperinflation. For sure, the rest of the world would be screwed before the US is over, as long as USD is still the reserve currency, and the US remains the most developed country in the world. Higher asset prices is bad news for those who don’t own assets yet, the inequality results from that is dangerous. Not sure whether I get what you are saying, and things are open for debate for sure. 🙂