What if finance is a solved problem?

Everyone knows everything, finance edition.

What is finance?

There are many ways to stylize this answer.

Matt Levine has done this several times, the most recent of which is his buckets of water analogy published this week.

This is just, you do the trades, then you undo the trades. You pour the water from one bucket into the other bucket, and then when that one is full you pour it back into the first bucket, because your job is pouring water and that’s what you’re paid for. Taking companies to one extreme of financial capitalism creates the conditions to move them back toward the other extreme. Someone has to tell companies to sell bits of themselves to pay down debt, reduce margins and sell more shares; someone has to charge management fees for doing it.

As Matt wrote earlier in this piece, finance is “moving not storage.”

Shuffle the deck chairs, as it were, and charge for it.

Matt’s piece this week came in response to Jeff Ubben’s comments given to the Financial Times. As I’m sure many readers saw, Ubben, the founder of activist fund hedge fund ValueAct, is leaving the firm to start a new fund focused on pushing companies to make changes that might generate positive societal and environmental impacts.

The thesis is that more conscientious companies will offer excess returns to investors.

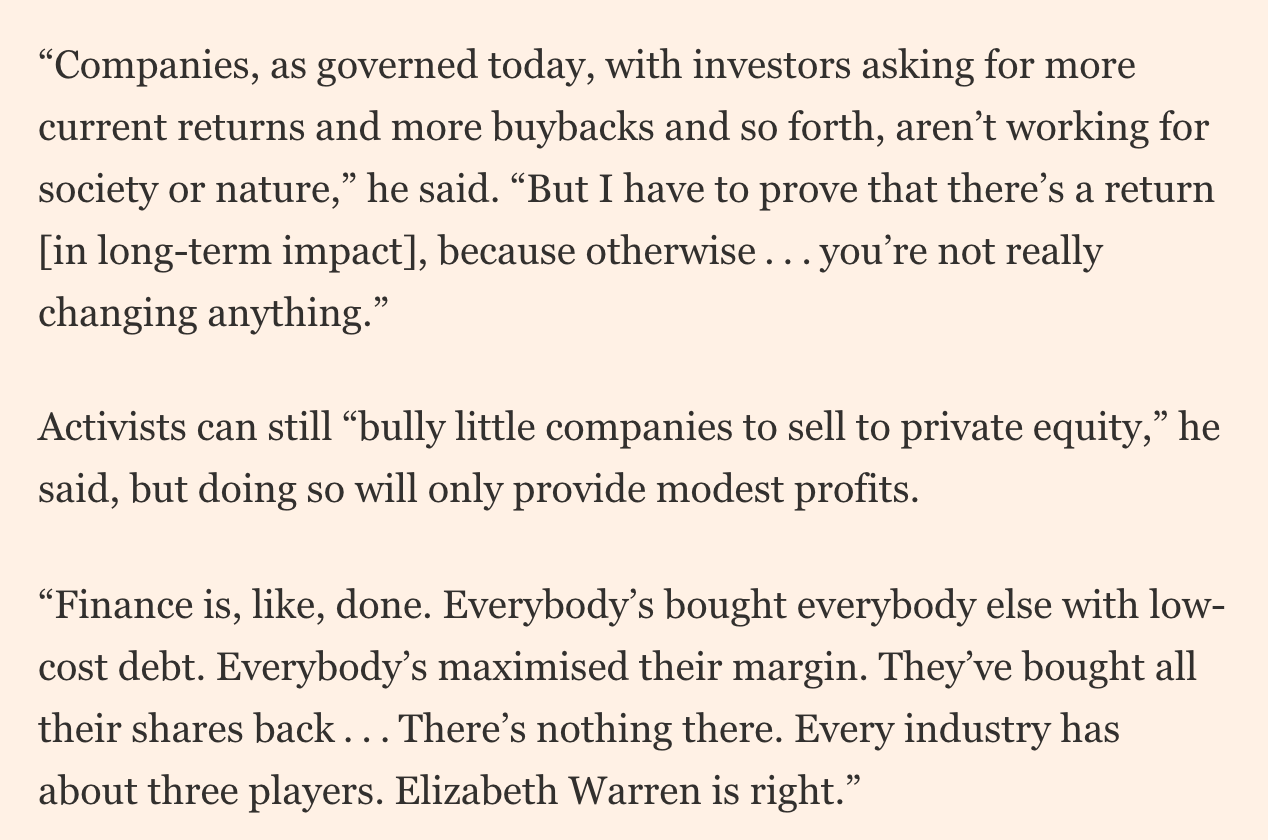

And on the way out, Ubben said this:

As Levine notes, of course, Ubben is not lamenting the end of finance but is instead congratulating himself on having solved the puzzle.

Finance isn’t over.

It’s just over to Jeff Ubben, who also happened to get all the answers right.

But… what if finance is over?

Like, in terms of jobs to be done the financial industry right now doesn’t offer anything almost everyone in and around the industry doesn't already know, even if the specifics of every deal or investment are different.

Think about the pillars of Ubben’s lament: leverage, consolidation, margins.

Everyone in the financial industry knows within tight tolerances how each of these factors would be used in the evaluation of a business you’d like to invest in, a business you’d like to acquire, or a business you’d like to sell.

No investor or banker gets on a call with another investor or banker and explains how an additional turn of leverage would change some business’s prospects during the first year of a merger integration and says anything the other person doesn’t know. In some time gone by this discussion might’ve been novel; in 2020 it is performative. Buckets and water.

A possible objection to this idea might be the current infatuation with businesses that generate recurring revenue. Investors now pay multiples of revenue instead of multiples of profit. This seems new and novel and like a conceptual innovation in a mature space. It would seem to call into question the idea that finance is solved.

But the preference for recurring revenue is, in the end, bolstered by Ubben’s thesis. This specific business trait is in fact a shortcut to what Ubben sees as the lamentable fate of all businesses — leverage, consolidation, expanding margins. Recurring revenue can easily be borrowed against, the stickiness of these customer bases create ripe areas for consolidation, and once you’ve acquired all your competitors growing margins naturally follow.

Ubben’s contention is that companies should try to pursue different goals. And, sure. But those goals are not compatible with what finance’s final answer, as it were, seems to be — lever, acquire, distribute.

And in thinking through Ubben’s comments this week, I was reminded of something famed gambler Jeff Ma told Patrick O'Shaughnessy back in December about baseball. In response to a question about which sport is the most interesting when view through the lens of analytics, Ma said baseball. And the reason why? Baseball is basically a solved problem.

Innovations like getting rid of starting pitchers, encouraging hitters to maximize for strikeouts and home runs, and putting on a shift for every batter are some of what has followed. As you’d expect, lots of old timers do not like this. Even Michael Lewis, who literally wrote the book on analytics and baseball, thinks the sport has gone too far.

That Michael Lewis started his career in finance, then started his writing career writing about finance, and then eventually migrated to writing about baseball is not an accident. Lewis’ financial career tracks with the mainstreaming of what Ubben thinks has ended; Lewis’ exploration of baseball tracks with the mainstreaming of what he and others now think has gone too far.

If we want to analogize this further, the rise in junk bonds in the 1980s were the financial industry’s version of baseball’s steroid culture in the ‘90s and early 2000s. In finance, the junk bond basically made it obvious that debt was good. In baseball, the steroid era made it clear that home runs are good.

Everything that followed in both areas more or less starts from the elevation of these previously misunderstood concepts.

And so if we accept that finance’s core problems are solved — and I am sure many readers will find this suggestion ridiculous — two questions follow: what next? And, so what?

But I think Ma already answered these questions, more or less.

What’s next for finance is what’s happening right now. Ma talks about how baseball has had to re-interpret its data set and push the edges of what everyone knows the answers to be. Home runs are the fastest way to score a run and the way to win a game is to score more runs. Therefore: maximize for home runs.

In finance, a lot of the re-interpretation has been around the data set’s simplest output: price. Investors, on balance, now pay more per dollar of future profit to buy or invest in a company not because the Fed said they had to but because competition has increased as the industry’s core question has converged on a few correct, settled answers. Lever, consolidate, profit. And so valuing a business on a multiple of the revenue it brings in instead of the profit it makes is an example of what would pass for price creativity.

Trying to buy good businesses at reasonable prices or whatever old-timey maxim you want to use is no longer actionable in and of itself because it isn’t anything every one of your competitors doesn’t already apply. Again: everyone already knows everything.

Another upshot of complaints about how baseball is played today is that they reveal the complainers don’t really love baseball as an abstraction, but baseball as they thought it would always be played. And the same goes for finance. As Jamie Powell at the FT outlined this week, Ubben has been a practitioner of everything he now laments and done quite well on that basis.

Which isn’t to say he doesn’t love finance, now or in the past. It’s just that when you face a solved problem you only have one option — change the problem.

For the sports analytics crowd, that has generally meant applying the techniques that lead to baseball’s solution to other sports. Basketball is not baseball. In this area, they’ve changed the problem.

For Jeff Ubben, it appears that simply trying to solve for something that is not financial is the pursuit that will set him free.

“When you’re talking about addressing climate change with a business solution, that is the biggest problem in the world,” Ubben told the FT.

“That’s like a 10-times-your-money deal.”

I guess we’ll see.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This. If someone sent this your way, or you haven’t done so yet, sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday.

If you agree, disagree, or just want to engage on any of the topics discussed in this letter, reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland.

Feedback is always welcome and highly encouraged.