All the words we cannot say

Why we struggle to capture how it feels to live in a time of pandemic

The only thing we talk about, read about, write about, think about is coronavirus.

We’ve read about young people suffering minor COVID symptoms dying of stroke. About Corona Toe. About couples that die within days of one another.

Back in March, when New York Magazine’s cover imploring readers to panic was on newstands, I remember walking around our neighborhood and saying that every tragic death, every medical oddity, all of these stories would get full coverage. Unfortunately this prediction has been mostly right.

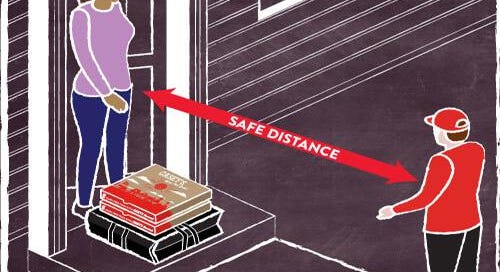

Every commercial right now is some brand reassuring us they are open for our business in this time of uncertainty. National pizza chains are pleased to inform us that no one touches our food after it’s cooked. I guess we should’ve been asking more questions back in January.

Early in this crisis, the internet’s darkest joke was our inboxes filling up with messages from companies we ordered underwear from in 2013 letting us know how they were preparing for COVID-19.

The virus, like everything else in this postmodern moment, has become content.

But as we wrote in an earlier edition of this letter, Shakespeare apparently never wrote about the plague because he decided there was nothing he could say. Foucault once said, “You always think that in a certain kind of situation you’ll find something to say about it, and now it turns out there’s nothing to say after all.”

And yet we can’t stop talking. Just check your Zoom calendar.

In his book on the 1918 Spanish flu “The Great Influenza,” John Barry notes that the Spanish Flu is almost non-existent in popular accounts of the era.

The disease has survived in memory more than in any literature. Nearly all those who were adults during the pandemic have died now. Now the memory lives in the minds of those who only heard stories, who heard how their mother lost her father, how an uncle became an orphan, or heard an aunt say, “It was the only time I ever saw my father cry.” Memory dies with people.

The writers of the 1920s had little to say about it. […]

John Dos Passos was in his early twenties and seriously ill with influenza, yet barely mentioned the disease in his fiction. Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald said next to nothing of it. William Maxwell, a New Yorker writer and novelist, lost his mother to the disease. Her death sent his father, brother, and him inward. He recalled, “I had to guess what my older brother was thinking. It was not something he cared to share with me. If I hadn’t known, I would have thought that he’d had his feelings hurt by something he was too proud to talk about. . . .” Barry, John M.. The Great Influenza (pp. 392-393). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

This is the part where my instinct is to talk about how social media has created authors out of us all. About how our collective inability to stop talking about the virus alters this course of history in which the deepest human sufferings go unsaid.

But modern accountings of this virus’ evils, how this virus is changing daily life, how this virus has forced us to make preparations we’d not ever imagined making, aren't saying anything to us we don’t already know.

We know this virus is to be feared, that our control over the world has been interrupted by nature’s assertion that we are but one small part of a bigger system. Medical curiosity stories are just reportage, textual procedurals. Warnings, but not even really that. Like the modern American diet, the average COVID story’s nutritional value is overstated by the flowery packaging.

And so we read the internet’s chaotic accounting of this time and silently carry with us the thousands who die every day, whose lives are counted as economic units — how many more job losses are we willing to bear to save another life?

As my former colleague Brett LoGiurato recently noted, we keep talking about “re-opening” as if there aren’t thousands of Americans dying all around us every day.

During his press conferences this week, Cuomo talked about the stubbornly high number of COVID deaths we’re still suffering here in New York. “Deaths lag!” the COVID-truthers scream, as if the dead aren’t warnings to the living.

But as Dan McMurtrie wrote on Friday, “The virus and its impacts are increasingly socially normalized and tolerable for Americans after 2 months stuck inside… If deaths are steady, the cumulative death toll that is socially allowable may be quite high.”

And indeed the death toll climbs and the stock market rises and our guard is slowly taken down. The novocaine is working.

Our public language — of money and power and deceit — allows us to make sense of debates over how you get an economy going after a downturn. We’re well-equipped to think in terms of profits and losses, opportunity costs and sunk costs, leverage and liquidity. And when commentators and politicians claim that some want the economy shutdown, or want people to get sick and die, because it might advance their policy goals we nod and accept that, while this might not be the view I have, it is certainly a view that someone could have.

Desiring pain and suffering for your enemies — political or otherwise — isn’t an idea that doesn’t make sense to us, even if we privately believe we would never play in that ball pit. But then again, this virus isn’t of this world.

“People write about war,” Barry writes. “They write about the Holocaust. They write about horrors that people inflict on people. Apparently they forget the horrors that nature inflicts on people, the horrors that make humans least significant.”

The 1918 influenza — a swifter, more garish version of dragged-out suffering COVID-19 asks its victims to endure — was too terrible to mention. If literature and art are about putting into words the things which cannot be said in polite company, influenza couldn’t even manage this.

“When the Nazis took control of Germany in 1933,” Barry writes, “Christopher Isherwood wrote of Berlin: ‘The whole city lay under an epidemic of discreet, infectious fear. I could feel it, like influenza, in my bones.’”

The track record of society’s inability to put into words the horrors that pandemics — that quiet, mass death in a population in a short amount of time — bring is already showing itself as a major impediment in our efforts to find footing in whatever the next phase of this crisis is.

Last week’s letter generated a fairly large reaction. Most of it positive in the sense that no one called me a bad person for writing it. But most of it negative because, well, the piece was kind of a bummer. But so is sitting indoors, so is fearing that anyone we see will get us sick, that we’ll get them sick.

It’s sad and jarring and mostly incomprehensible that “real life” isn’t coming back this year, that we’re going to be forced to redefine “real life” when this is all over. And sure, in time we’ll forget what normal meant in 2019 and we’ll view something else as an adequate replacement. None of this means the experience of being alive right now isn’t deeply sad.

Now, if our track record is spotty when it comes to putting the emotions and dread pandemics induce then humanity’s track record is far stronger when it comes to adapting to wholesale changes imposed on us from the outside.

When it comes to positive messages, this is about all I’ve got: I’m sure one day in the future it will be fine.

Whether art will fail to help this process is an open question. Whether these words and others’ help us heal will never be known. All I know I can do is write; you’re free to read or unsubscribe. Everyone has to cope.

And while early returns on what this period will teach us might not be super encouraging, it’s a crisis and we’re all just trying our best.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This. If someone sent this your way or you haven’t do so yet sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday morning.

If you agree, disagree, or just want to engage on any of the topics discussed in this letter reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland.

Feedback is always welcome and highly encouraged.

When I started this project six months ago, a private promise I made to myself is that it would not turn into a high school level book report newsletter.

Asking for your attention once a week just to tell people about how much I’ve been reading didn’t seem particularly useful.

But I did read John Barry’s book “The Great Influenza” recently and walked away with a few high-level takeaways for this current pandemic. This addenda is not expected to be a regular feature of this newsletter.

This pandemic is going to linger. I believe that “re-opening” is going to be a one way street, hence the caution we’re seeing from many governors, but in 15 months there will still be people getting sick with COVID-19 and a vaccine is going to be our only solution. Influenza is a brutal disease that can rip through a population in 6 weeks. Herd immunity is something that inadvertently becomes a strategy for dealing with influenza outbreaks — it’s sort of our default approach considering how frequently the annual flu vaccine protects just a small percentage of recipients — but the incubation and illness period for COVID-19 has taken this off the table. Not enough people have gotten sick during this initial outbreak for anything approaching herd immunity to be the case and our mitigation efforts will likely keep the percent of the population that gets sick with COVID-19 low. This is good. The bad is that it means this disease is a part of our life for a long time. (Barry worked with the team at the University of Minnesota and wrote about this idea in a piece published earlier this month.)

Influenza pandemics are something we still need to be very worried about. Barry writes: “The world looked black. Cyanosis turned it black. Patients might have few other symptoms at first, but if nurses and doctors noted cyanosis they began to treat such patients as terminal, as the walking dead. If the cyanosis became extreme, death was certain. And cyanosis was common. One physician reported, “Intense cyanosis was a striking phenomenon. The lips, ears, nose, cheeks, tongue, conjunctivae, fingers, and sometimes the entire body partook of a dusky, leaden hue.” And another: “Many patients exhibited upon admission a strikingly intense cyanosis, especially noticeable in the lips. This was not the dusky pallid blueness that one is accustomed to in a failing pneumonia, but rather [a] deep blueness.” And a third: “In cases with bilateral lesions the cyanosis was marked, even to an indigo blue color. . . . The pallor was of particularly bad prognostic import.” Then there was the blood, blood pouring from the body. To see blood trickle, and in some cases spurt, from someone’s nose, mouth, even from the ears or around the eyes, had to terrify. Terrifying as the bleeding was, it did not mean death, but even to physicians, even to those accustomed to thinking of the body as a machine and to trying to understand the disease process, symptoms like these previously unassociated with influenza had to be unsettling. For when the virus turned violent, blood was everywhere.” Barry, John M.. The Great Influenza (pp. 236-237). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The 1918 war effort in the U.S. was a major part of spreading influenza. Young men were brought to training camps from all over the country and the virus spread like wildfire through these cantonments. At Fort Devens in Massachusetts, “On September 7, a soldier from D Company, Forty-second Infantry, was sent to the hospital. He ached to the extent that he screamed when he was touched, and he was delirious. He was diagnosed as having meningitis… In the overcrowded barracks and mess halls, the men mixed. A day went by. Two days. Then, suddenly, noted an army report, “Stated briefly, the influenza . . . occurred as an explosion.” It exploded indeed. In a single day, 1,543 Camp Devens soldiers reported ill with influenza. On September 22, 19.6 percent of the entire camp was on sick report, and almost 75 percent of those on sick report had been hospitalized. By then the pneumonias, and the deaths, had begun. On September 24 alone, 342 men were diagnosed with pneumonia. Devens normally had twenty-five physicians. Now, as army and civilian medical staff poured into the camp, more than two hundred and fifty physicians were treating patients. The doctors, the nurses, the orderlies went to work at 5:30 A.M. and worked steadily until 9:30 P.M., slept, then went at it again. Yet on September 26 the medical staff was so overwhelmed, with doctors and nurses not only ill but dying, they decided to admit no more patients to the hospital, no matter how ill.” Barry, John M.. The Great Influenza (pp. 187). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Um, Woodrow Wilson might’ve gotten influenza and then lost his mind and signed the Treaty of Versailles in a compromised state? The argument is, more or less, that influenza led to the rise of Hitler and, in turn, World War II. Taken to its most extreme, there’s an argument that the entire death toll of World War II is attributable to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. “Influenza did visit the peace conference. Influenza did strike Wilson. Influenza did weaken him physically, and—precisely at the most crucial point of negotiations—influenza did at the least drain from him stamina and the ability to concentrate. That much is certain. And it is almost certain that influenza affected his mind in other, deeper ways. Historians with virtual unanimity agree that the harshness toward Germany of the Paris peace treaty helped create the economic hardship, nationalistic reaction, and political chaos that fostered the rise of Adolf Hitler. Barry, John M.. The Great Influenza (pp. 387-388). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. The full case is made in chapter 32, for interested parties.

It’s called the Spanish Flu because Spanish newspapers widely reported on the influenza outbreak after King Alfonso XIII got sick. (171) The press was heavily censored in countries that were main protagonists in the war to avoid bad news. And so mass death and sickness spread by word of mouth and by way of the Spanish press.

We’re still learning about the 1918 pandemic today and all enthusiasm about vaccines, treatments, and what we’re going to understand about this virus needs to be tempered. The ambiguity of science isn’t something we’re well-equipped to handle in a world of Google searches. But the lack of answers about COVID-19 today isn’t a bug but a feature of the scientific process that surrounds trying to contain, treat, trace, and identify this current viral outbreak and all the others that will come our way in the years ahead.