Welcome back to Late, a newsletter about things we haven’t stopped thinking about.

If someone sent this your way or you found this letter through Twitter or other channels, sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish on Sundays.

Late is free to read and will remain that way indefinitely. More than 2,400 readers currently enjoy Late and we hope to this audience keeps growing in the years ahead.

If you like what you’ve read, spread the word by sharing this post or forwarding to a friend. We’re always surprised by the strength of word-of-mouth recommendations.

And now: Warren Buffett.

Like all Dads, my father loves to jump into the middle of a discussion and say: “Hold on, let’s think about this.”

What follows is some simplified set of examples to blur out all the particulars and get down to answering a question that asks something like, “Is this a good idea?”

We can save the discussion of why it seems all Dads converge on a handful of shared behaviors for another time. There is, as far as I know, no official Dad Book that outlines how one goes about adopting these specific tics. And yet every Dad manages to.

But so this intentionally over-simplified breakdown of what something is worth, or how long something might take, etc., is also a major convention of certain kind of business analysis. We can call this “quick and dirty” math. We can call it a “high level” view. A “back of the napkin calculation,” if you like.

But I like to think of all this as Buffett Math.

Let’s take an example from Warren Buffett’s 2015 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders. In this letter, Buffett wrote that, “The babies being born in America today are the luckiest crop in history” and leaned on some good old fashioned Buffett Math to get us there.

American GDP per capita is now about $56,000. As I mentioned last year that – in real terms – is a staggering six times the amount in 1930, the year I was born, a leap far beyond the wildest dreams of my parents or their contemporaries. U.S. citizens are not intrinsically more intelligent today, nor do they work harder than did Americans in 1930. Rather, they work far more efficiently and thereby produce far more. This all-powerful trend is certain to continue: America’s economic magic remains alive and well.

Some commentators bemoan our current 2% per year growth in real GDP – and, yes, we would all like to see a higher rate. But let’s do some simple math using the much-lamented 2% figure. That rate, we will see, delivers astounding gains.

America’s population is growing about .8% per year (.5% from births minus deaths and .3% from net migration). Thus 2% of overall growth produces about 1.2% of per capita growth. That may not sound impressive. But in a single generation of, say, 25 years, that rate of growth leads to a gain of 34.4% in real GDP per capita. (Compounding’s effects produce the excess over the percentage that would result by simply multiplying 25 x 1.2%.) In turn, that 34.4% gain will produce a staggering $19,000 increase in real GDP per capita for the next generation. Were that to be distributed equally, the gain would be $76,000 annually for a family of four. Today’s politicians need not shed tears for tomorrow’s children.

Indeed, most of today’s children are doing well. All families in my upper middle-class neighborhood regularly enjoy a living standard better than that achieved by John D. Rockefeller Sr. at the time of my birth. His unparalleled fortune couldn’t buy what we now take for granted, whether the field is – to name just a few – transportation, entertainment, communication or medical services. Rockefeller certainly had power and fame; he could not, however, live as well as my neighbors now do.

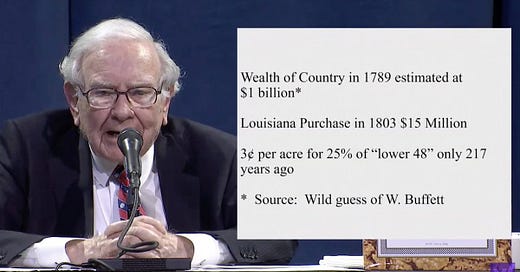

The Berkshire annual meetings might be an even better place to find these bits of Buffett Math in the wild. At last year’s meeting, Buffett opened with a series of slides that argued this same point.

For example:

One hopes this format is revived in two weeks’ time.

Last week we saw Jeff Bezos engage in the practice at the highest level.

In his annual letter to shareholders — his final as Amazon CEO — Bezos pitched the annual value of a Prime membership as creating $126 billion of value for customers while Amazon Web Services similarly creates $38 billion of value.

Let’s just look at the breakdown on Prime.

Customers complete 28% of purchases on Amazon in three minutes or less, and half of all purchases are finished in less than 15 minutes. Compare that to the typical shopping trip to a physical store – driving, parking, searching store aisles, waiting in the checkout line, finding your car, and driving home. Research suggests the typical physical store trip takes about an hour. If you assume that a typical Amazon purchase takes 15 minutes and that it saves you a couple of trips to a physical store a week, that’s more than 75 hours a year saved. That’s important. We’re all busy in the early 21st century.

So that we can get a dollar figure, let’s value the time savings at $10 per hour, which is conservative. Seventy-five hours multiplied by $10 an hour and subtracting the cost of Prime gives you value creation for each Prime member of about $630. We have 200 million Prime members, for a total in 2020 of $126 billion of value creation.

So the Prime equation is: Prime Value = ((S*V)-C)*M where; S=annual time savings, V=time value, C=cost of Prime, and M=Prime members.

I think they teach this in like 7th grade. Maybe in the 9th grade you have to define each of S, V, C, and M in more detail. But who knows, I wasn’t very good at math in school.

So we add this number to the Buffett Math-money earned by third party sellers, comp paid to Amazon employees, and earnings retained for shareholders, and Bezos argues that Amazon created $301 billion for its various stakeholders in 2020.

If each group had an income statement representing their interactions with Amazon, the numbers above would be the “bottom lines” from those income statements. These numbers are part of the reason why people work for us, why sellers sell through us, and why customers buy from us. We create value for them. And this value creation is not a zero-sum game. It is not just moving money from one pocket to another. Draw the box big around all of society, and you’ll find that invention is the root of all real value creation. And value created is best thought of as a metric for innovation.

Okay, sure.

I don’t really disagree with Bezos’ framework insofar as it views a corporation’s output in a more Kalecki-friendly mode with traditional balance sheet liabilities like employee comp seen as an investment in economic activity which thus benefits the company’s future growth and so on. As a general idea, it’s more productive to frame a company’s role within the economy like this rather than, say, the other famous Bezosism that “your margin is my opportunity.” Which represents the kind of zero-sum thinking that very much turns the public towards viewing corporations as nothing but rent-seeking vultures trying to make your financial foundation more precarious and charging a fee to do so.

But in wielding Buffett math to make his case for the value of Amazon’s most famous business — its Prime membership — Bezos also breaks down the complex issue of “What is Amazon Prime worth?” and puts it into middle-school level math pretty much anyone can do.1

That two of the world’s richest men and most prominent business leaders like to lean on oversimplified examples of how their businesses operate or how to understand the U.S. economy can go a few ways.

Buffett Math is no doubt a cutesy way for some of the world’s most ruthless capitalists to explain away and justify their actions which have had negative consequences for customers and the country at large.

Recent reporting around conditions facing Amazon’s drivers and the tactics taken by Berkshire-owned Clayton Homes to exploit America’s poor are but two examples of the less savory parts of these empires. These sorts of arguments also, as Post Market shows us, get pretty much right up to the line of being complete bullshit and might even cross it.

But Buffett Math does, to our mind, show that seemingly intractable problems of Money and The Economy are often simple ideas overcomplicated by those trying to protect the appearance of expertise. And perhaps serves to reinforce, for Bezos, Buffett, or any other luminary outlining a rudimentary framework for their business approach, that an idea they’d once believed was simple has in fact remained so. In almost every one of his annual letters, Buffett takes on an accounting or valuation concept and approaches it by similar means to say: here is what Berkshire is actually doing.

The exercise of using Buffett Math to break down a problem is thus about trying to reinforce, for yourself and an audience, that the seemingly arcane can in fact be straightforward.

The financial world of discounted cash flows and adjusted EBITDAs — among hundreds of other valuation measures — can also be boiled down to basic algebra and the answering of a simple question: “Do you think [this thing] is worth it?” The answer is yes or no.

A standard convention of the investment management business is to name your firm after a Greek philosopher and then use famous quotes as epigraphs to a several-thousand-word-long investor letter that only tangentially addresses investment decisions and mostly serves to remind clients that their fund manager went to Harvard.

But the investment business is a simple one: make investments that will earn positive risk-adjusted returns for clients within your mandate.

In other words, tell people what they can expect from you and then do it. No one cares if you read the Classics in undergrad.

Working to keep questions of economic value creation in their simplest terms also opens up for us the space to take on life’s actually important questions with the enthusiasm they deserve.

And reminds us that the value of Amazon Prime doesn’t really matter. It’s just something to talk about.

Right after this bit of the letter, Bezos breezes through the union busting and labor concerns that have been the subject of the majority of media attention around Amazon over the last year. Dedicating a few sentences of your primary communication with shareholders to discuss bathroom breaks is a great example of something you never want to have to say. But considering some of the PR tactics we’ve seen from Amazon in recent weeks, it’s probably best if the guy who got the company here takes a turn defending the company; the official corporate Twitter account just isn’t cutting it.