Long-term thinking and coronavirus

How supposed long-term thinking renders the present indecipherable and dangerous

The point of this newsletter is explicitly not to be news.

In the 14 editions I’ve written before this morning’s, only a few times have I veered into what I think might’ve been “newsy” editions. For instance, I’ve written about NBA ratings (boring!) and the crazy swings in shares of Tesla (more interesting!).

But during this past week, it became increasingly hard to conceive of writing about anything but coronavirus. There are almost infinite angles to be taken by reporters, medical professionals, policymakers, and commentators when it comes to discussing this technically-not-yet-a-pandemic viral outbreak.

A still-alive take on the coronavirus that I see in my Twitter feed at least daily is some stat about how many more people will die in car crashes, or from cancer, or from the common flu than will die from coronavirus.

This broad, high-level “perspective” on how dangerous this virus might be to the general population is supposed to, I think, make us feel better about the dangers posed by this virus. Or at least feel calmer, more complacent, more sober about something that has ginned up a lot of hysteria in the public.

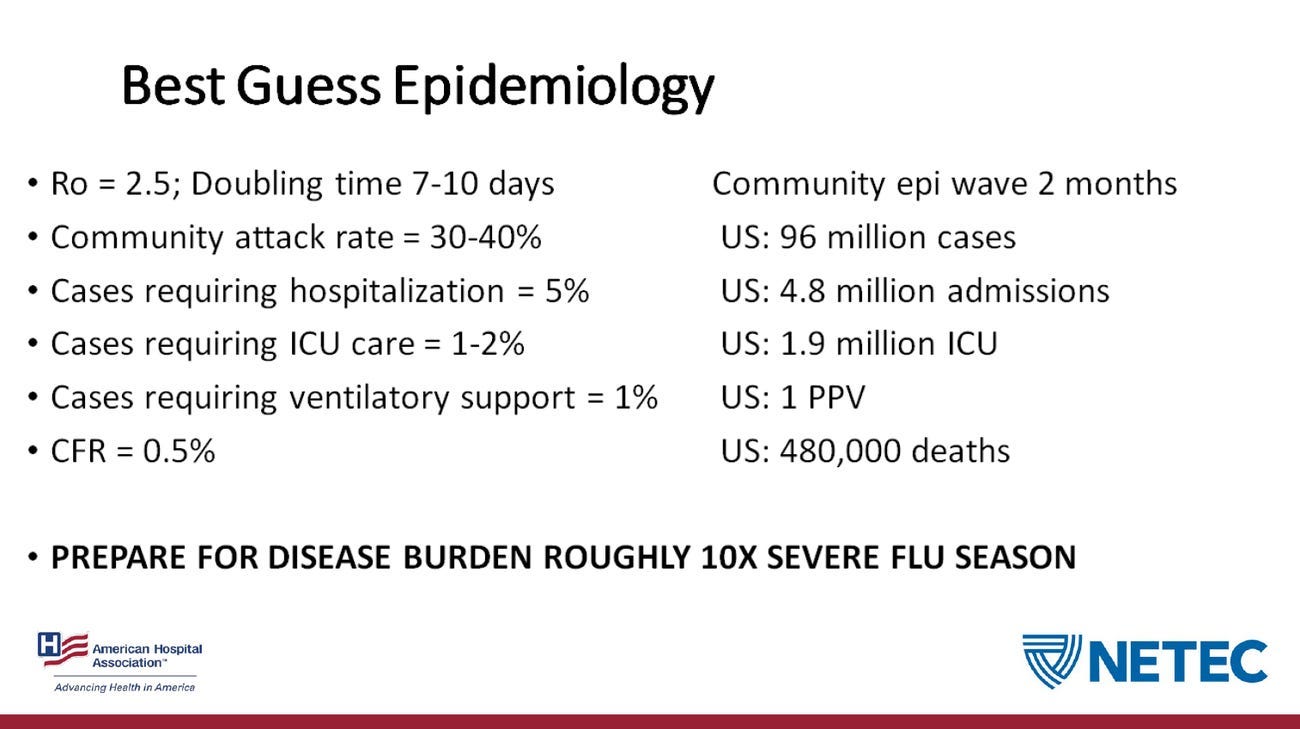

There are several problems with this worldview, not the least of which that it is way out of line with scenarios actual medical professionals are preparing for.

Two weeks ago, this newsletter looked at the experience of buying things on Amazon and the internet’s trend towards taking everything you once loved and making it worse. This is a business-focused adaptation of Balk’s Third Law of the Internet: “If you think The Internet is terrible now, just wait a while.”

In that Amazon post I noted that the Pinkerian response — a retort inspired by the Stephen Pinker-style view that literally everything about being alive today is better than it was in the past — is basically a catch-all for refuting these sorts of first world problem complaints that an obscene convenience enabled by technology has been downgraded to a merely incredible convenience. This explaining away of present, local frustrations with services and goods that are broadly improved from the past, however, is precisely How Things Got Here.

And arguments about coronavirus being “just as bad as the common flu” are just another repurposing of that same line of thinking. Ignoring the threat this virus poses in favor of a base case that is no longer in play doesn’t make you enlightened or possessing a thoughtful long-term view, but impairs the ability to see what is actually happening on the ground.

A few weeks back, David Schawel made an analogy about coronavirus and investing I’ve thought a lot about. “The US without coronavirus testing is like a quarterly marked private stock portfolio in the middle of a plunging market,” Schawel wrote on Twitter.

I said at the time this was an example of the “private equity mindset” taking over everything. Which might not be totally fair to private equity and what those firms try to accomplish.

But I do think it’s fair to say that a big part of private equity’s value proposition is time. They offer investors and the businesses they invest in a certain amount of time to execute on plans that, PE argues, is not afforded to companies by public markets. Or in the case of smaller businesses, PE offers time and money that cannot be obtained from traditional financing sources.

And this time and money is really about letting operators avoid making wholesale changes in the face of short-term pressures. It is an offer that is derivative of the “broadly, things are better” worldview.

If you can allow a business or an individual to ignore a problem that is right in front of them in favor of something better out there, why wouldn’t you? In certain business contexts, this might make sense. A competitor enters a new market and with PE backing, perhaps you are able to avoid an ill-fated copycat strategy public investors might foist upon you. (Alternatively, some will argue that PE backing might make you more likely to chase this strategy because you have more capital and higher return expectations, but a longer time to let the bumps smooth out before you need to be sold or taken public. And so on.)

Taken to broader extremes, however, this long-term approach to reality I’m calling the “private equity mindset” ends up creating an irreality, a warped truth about what matters, when it matters, and how we ought to handle it.

The problem presented by coronavirus is not, strictly speaking, that the virus is more deadly, or more widespread, or more contagious than the common flu. It may be all of these things. It may not. We are learning a lot about this virus and how it spreads and who it kills and how it is transmitted every day.

Noting that the virus has killed over 3,500 people and officially infected more than 100,000 globally and comparing this to the number of people who get the common flu and die from it each year is not making the point people citing this data think it is making. But even engaging in a numeracy debate about what both sets are saying isn’t capturing what I think the Pinkerian worldview occludes.

Because by citing the broadest possible data to ignore the local concerns presented by a novel virus, or an inability to individually obtain affordable healthcare, or difficulty shopping on Amazon without inconvenience, you are not opting to take a “long-term view” but instead opting to have no view at all. It is the politics of no politics.

As far as I can see, the dangers presented by COVID-19 are several but most pressingly: that it is spreading faster than we can test, that it will overburden already stretched healthcare systems, and that our best method for limiting the virus’ spread (social distancing) will create immense economic pressures around the globe. (The questions around how to measure the virus’ impact has, predictably, devolved into VC Twitter explaining why only they understand exponential growth.)

But it is the first of those three major issues COVID-19 currently presents that gets to the heart of why this PE-inspired, long-term, look-through mindset leaves you blind, not enlightened.

If you can’t accurately mark your book to market — or if you only have to report your numbers quarterly when the world is falling apart around you right now — you can still pretend to be something you’re not. The Trump administration is currently arguing the virus is “relatively contained,” but can only do so because our inability to test for COVID-19 has kept infection counts artificially low.

The administration can’t — or chooses not to — mark its virus book to market. And so it pretends the outbreak is something it isn’t.

And while it’s certainly jarring to see Larry Kudlow become the official mouthpiece of the White House’s response to the most serious public health crisis in over a decade, that our government is also choosing to broad stroke-away the seriousness of coronavirus is a moment we’ve been working towards for years.

It comes on the heels of a decade during which internet (and irl) culture was built around everyone trying to out-indifferent one another. That trying to understand and respect the dangers of a novel coronavirus seems to leave you looking either like a prepper or a pollyanna shouldn’t be surprising. A middle lane of earnest concern is incompatible with the world the internet makes us live in.

Which brings to mind Balk’s Second Law: “The worst thing is knowing what everyone thinks about anything.”

Especially when it comes to a virus no one really knows that much about.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This. If someone sent this your way or you haven’t up yet, make sure to do so below so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday morning.

If you agree, disagree, or just want to weigh in on today’s newsletter, reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland. Feedback is always welcome and highly encouraged.