Hello and welcome to Late, a newsletter about trends, fads, ideas, complaints, or whatever else it is I haven’t stopped thinking about.

If someone sent this your way and you haven’t do so already, make sure to sign up below so you never miss an issue.

We publish each Sunday. Or at least most Sundays. Or on Mondays when that Monday feels like a Sunday. Like today.

And now, bubbles.

A great American tradition is engaging with advertisements as entertainment.

Which is, after all, what they really are.

Someone on Twitter this week surfaced an old interview with George Harrison on the Dick Cavett Show in which George talked about American television and how aggressive the adverts (one of my favorite Britishisms) are.

“You don’t know if it’s the commercial or the show,” Harrison says.

Or as Neil Postman writes in Amusing Ourselves to Death:

The television commercial is not at all about the character of products to be consumed. It is about the character of the consumers of products… What the advertiser needs to know is not what is right about the product but what is wrong about the buyer… The television commercial has oriented business away from making products of value and toward making consumers feel valuable, which means that the business of business has now become pseudo-therapy. The consumer is a patient assured by psycho-dramas. (pp. 128)

And as the meme says — men will literally write a Substack newsletter about insurance commercials and the stock market instead of going to therapy.

And so: I’m guessing many readers have seen the Progressive commercials with Dr. Rick, the guy who tries to help prevent new homeowners from becoming their parents.

These commercials are memorable enough that I’ve now had conversations with people about which ones they like more. During this weekend’s football games, there was talk about why they seemed to play the “Dr. Rick gives a seminar” version of the ad instead of the “Dr. Rick tells the guy at the hardware store that no one needs to know which grout brush he thinks is best” cut. The latter, it was argued, is funnier.

And so but one of these commercials features three millennials-turned-homeowners-and-so-now-turned-Boomers standing in a store while someone with dyed blue hair walks by.

“We all see it,” Dr. Rick says, reminding these dads-in-training there’s no reason to comment out loud on the hair color choice of a younger person who decided to do something you personally wouldn’t do.

And yet as everyone who has been embarrassed by their parents in a public place knows, the dads cannot stop: “Blue hair!”

Which is kind of how it feels to look at the stock market these days.

The blue haired people are the SPAC sponsors, the YOLO Robinhood crew, the EV pumpers, the crypto dunkers. The blue haired market participants are making money and telling the haters in Twitter replies that they can have fun staying poor.

Everyone else is just a frumpy, middle-aged guy standing around saying those trades and trends and strategies are weird and different, writing things like “This won’t end well!” as if this anodyne not-advice will connect as a real warning to those having more fun than khaki-and-vest wearing mid-career private wealth VPs. And then there is Jeremy Grantham: “The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully-fledged epic bubble.”

The lesson of the commercial, of course, is that there’s really no role for the Boomers here. As our commercial’s life coach reminds us — “We all see it.” There is no value in pointing out something that isn’t conforming. No one cares that you noticed the thing literally everyone else also noticed. So but in thinking about Late this week, it was hard to imagine writing about much else besides SPACs and the pockets of today’s market that are clearly in a bubble.

According to SPAC Insider, there have been 53 SPAC IPOs through the first ten trading days of 2021. Torrid would be the word to use here. There are currently 274 SPAC sponsors, or blank-check vehicles in which money has been parked but not deployed, searching for a target.

Every morning on Yahoo Finance we take the feed from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange where a company or cause or person rings the opening bell. Lately, it seems that every day the podium is occupied by someone from an outfit like Big Sky Adventures Acquisition Corp, ticker: BSKY.U, which might cause the uninitiated to think they offer guided tours of Gallatin County, Montana and nearby Yellowstone National Park, when this is actually just a SPAC named for one of the sponsor’s executive team’s favorite vacation home.

A few months back I looked at SPACs in the context of public markets becoming the new private markets. The idea was that whereas the last investment cycle saw the rise of PE and VC as the place to get your moonshot business funded, that center of gravity has shifted to the public markets and the SPAC vehicle is part of the reason why.

There can be lots of reasons for this energy transfer between private and public markets — performance chasing, envy, boredom with increasingly passive public markets, and so forth. I think about someone like Gregg Lemkau, the former co-head of investment banking at Goldman who left late last year to take a spot with one of Michael Dell’s funds. I am guessing he will be part of a SPAC sponsor team soon. And why not? After years of doing good old fashioned M&A and investment banking at Goldman Sachs, doing a SPAC-sponsored go-public deal is like the vacation-home version of his former life. All the fun and the glory and half the work.

Frank Rotman had an interesting thread this week on SPACs and posited that part of the appeal for businesses and investors is that this structure empowers companies to outline their vision of the future while the traditional IPO process is focused on a company’s past. Which, sure.

For an emerging growth business the S-1 is a buzzkill, a total bummer, a series of audited financials showing perpetual losses and legally requiring risk disclosures that warn you may never hit profitability. Disclosures that become an annoying story in the business press in a classic “both true and not true” kind of deal. The document is full of boilerplate negativity. It’s hard to wash that stink off. This is what you pay the bankers for.

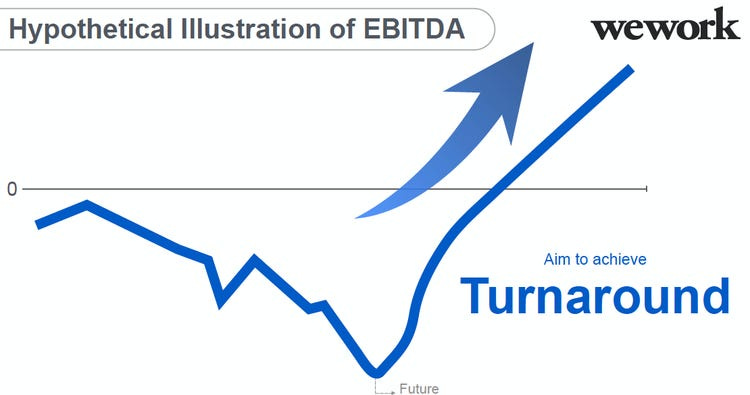

But on the other hand, the SPAC boom has led to dozens of investor presentations in which a version of the Softbank WeWork slide is presented without irony.

And yes, eventually companies going public via SPAC have to do a formal S-1 like everyone else and say all the bad things about their business and reveal just how little money is coming in the door and so on.

To which the reaction is usually:

Over at Yahoo Finance this week, we highlighted work from Upslope Capital’s George Livadas, who is short a basket of SPACs and skeptical of the space in general.

Livadas outlined that the first full run of financials from recently SPAC’d businesses is a potential challenge for these stocks in the new year “given the number that have provided investors with laughably aggressive earnings forecasts to justify transactions.” Adding that it makes sense to put a short position on today because of how fast things come and go in the modern market — the 2017-era crypto crash and 2018’s busts in short vol strategies and pot stocks came and went so fast that by the time you knew the bubble was bursting it had already burst.

The SPAC market really does resemble a modern version of the 90s tech bubble. Through mid-January, I counted 21 announced or closed EV-related (electric vehicle) SPACs that had a combined pro forma enterprise value of almost $120bn. This group is expected to generate less than $700mm of sales in 2020 for a combined EV/Sales multiple of about 175x. Of course, virtually every EV SPAC has offered up hockey stick-shaped projections, with the group forecasting a 230% revenue CAGR through 2022 (Competition? What competition?). This implies a 16x 2022 revenue multiple, about in-line with Tesla, the poster-child for bubble stocks in general. Except, unlike Tesla, the vast majority of EV SPACs have little scale and often little-to-no working product today. But, SPAC investors are optimistic about the future and willing to pay fat premiums to transaction prices.

Historically, the SPAC free lunch was mostly paid for by retail investors. Institutions owned shares at the IPO price and generally sold to retail for a premium upon announcement or closing of a deal. Inevitably, such premiums often proved misguided. Projections provided by sponsors/management when pitching the viability of a deal (for which they get compensated for simply closing) are often far too rosy. Apparently, there’s a reason many previously-unheard-of businesses opted out of going public via the traditional IPO route, which forbids such projections. But the current SPAC boom has been a free lunch for everyone involved thus far.

And as I wrote in that Yahoo piece, that we’re even discussing SPACs as an asset class when, as we’ve written previously, they are a compensation and financing scheme first, second, and third, sort of proves the bubble thesis. When a derivative part of your business plan becomes the main event you’re officially in over your head.

Speaking of derivatives, the focus on the SPAC structure might also be distracting from a distinct but related bubble breaking out in public markets today, which is happening in the green energy space.

George Pearkes writes at Business Insider this weekend:

Chinese electric carmaker Nio trades 62 times its revenue and is worth almost $100 billion. Electric truck company Nikola traded up to a market value of nearly $30 billion last summer with little concrete progress towards actually building its products. European wind energy giants Vestas and Siemens Gamesa trade around 100 times their earnings.

Since mid-2018, MSCI's Global Alternative Energy Index has more than doubled. Its biggest members are offshore wind companies like Vestas, Orsted, Siemens Gamesa, and Northland Power, as well as solar stocks like Enhpase, SolarEdge, Xinyi, Sunrun, and First Solar.

Pearkes notes, however, that not all bubbles result in economy-wide financial ruin and can in fact birth the leaders of the next cycle.

The opportunity offered by an equity market bubble in green stocks is not one for everyone to get rich, but to speed up the investment in research and development, infrastructure, and deployment of technologies that will allow a decarbonized future.

A similar process played out in the last tech bubble. Huge valuations and capital raises ultimately financed much of the internet infrastructure which allowed for "Web 2.0" innovation. Giants like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Netflix are the result.

So long as investors and management teams don't apply much leverage (that is, borrowed money), the ripple effects of an equity market bubble are less likely to spiral across the economy as they did after the housing market crash.

Which brings me all the way back to one of Late’s earliest posts, which covered Jerry Neumann’s 2015 essay about the deployment age.

The exciting part of Neumann’s thesis implies we’re at the beginning of a potentially 20+ year cycle during which we will realize the full potential of all the tech we’ve seen hyped over the last few decades. The early returns on this idea are things like Uber and Lyft changing transportation, Spotify giving you access to basically every song ever made for $10/month, and Instagram creating an on-demand mall. These services are unlocked by the ubiquity of internet-connected phones. Technology that was built during the 1990s tech bubble is being efficiently and effectively deployed 20 years later. [...]

The less exciting part (for some, at least) of the deployment age is that we’re now entering a period where innovation is iterative, not transformative. As thesis statements for what this shift means goes, I think this brief passage says it best:

The zeitgeist changes from creative destruction to creative construction. Financial capital pulls back and production capital takes over the funding of innovation.

“Financial capital” can be loosely defined as “hot money” or just “investor capital.” This is money looking for returns on capital, not business success. During the current cycle this goes from junk bonds to the rise of LBOs in the 1980s, then morphs into retail investors speculating in tech stocks in the ‘90s and adult entertainers becoming house flippers while banks turn their balance sheets into Jenga towers of derivative risk in the 2000s.

Then it unwinds.

Given that it’s a mere 14 months later and we’re writing about hot money flows into a new sector of the market, perhaps it is worth revisiting some of these financial vs. production capital assumptions. The deployment may not yet be upon us.

Then again, if we apply the “everything happens faster and more often” framework outlined by Livadas earlier in this post — which is definitely a baseline assumption of the Late worldview — then ought not to be a surprise that a shift from financial to production capital in big tech is concurrent with, and not antecedent to, the latest hot money flows in an adjacent but distinct industry like electrified self-driving cars.

Increasing rates of changes within each successive business cycle would dictate that big tech’s transition from financial to production capital need not be completed before the next generation of financial is deployed en masse.

The outgrowth is our modern market full of fast-forming micro-bubbles.

And another thing to remember about these bubbles is that they aren’t hard to spot. If you’re ever even a little bit on the fence about whether a hot sector is a bubble then you know it’s not.

The reason so much time was spent explaining why the performance of the FAAMG stocks from 2015-2018 wasn’t particularly interesting is because some stocks going up more than others doesn’t make a bubble. Stocks, in general, tend to go up. Quickly, even.

But an actual bubble is unmissable.

It looks like this.

And like this.

And like this.

So what’s going to happen to a lot of these renewable-focused stocks — both those trading today and those set to come public via SPACs in the near future — is that they will trade lower.

Some stocks fall more than others. Some of these companies will be winners in a newer, greener economy. Some of these companies will not make it. One of these companies might even be the “Amazon of EVs” or whatever it is that investor deck promises.

But there are many companies today whose stock is trading like they will be the primary winner of a winner-take-most market. Obviously, this cannot hold.

Anyone can do whatever they want with this information — short stocks, buy stocks, bookmark it to laugh at me later, and so on.

But it’s hard right now to stop myself from becoming my parents, hard to just not say anything and let the market play it out.

Because we all see it.

And now I understand what Neil Postman really means.