There's one way to do this

Why the list of acceptable strategies for solving problems has gotten so short

Welcome to I’m Late to This, a newsletter about things I haven’t stopped thinking about.

New subscribers — and this week there are quite a few of you — welcome.

If someone sent this your way or you haven’t signed up yet, sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday morning.

And now, I will break a rule.

My old boss Joe Weisenthal has a guiding principle for content that will rarely steer anyone wrong: most books should be articles, most articles should be posts, most posts should be tweets, most tweets should be retweets.

Alternatively: never tweet.

But this week I tweeted something and I want to expand on it here.

Against my better judgement, I’m going to reverse-Weisenthal this thing.

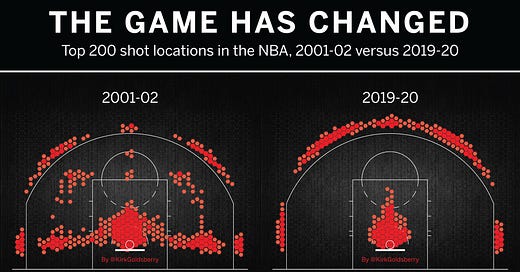

This week, basketball writer Kirk Goldsberry tweeted out this graphic from his book SprawlBall: A Visual Tour of the New Era of the NBA.

The basketball fans reading this will already know, without seeing the graphic above, how sharp the divide is between an average NBA game in 2020 and how the game was played 20 years ago. But fear not: this is not going to be a post just about basketball.

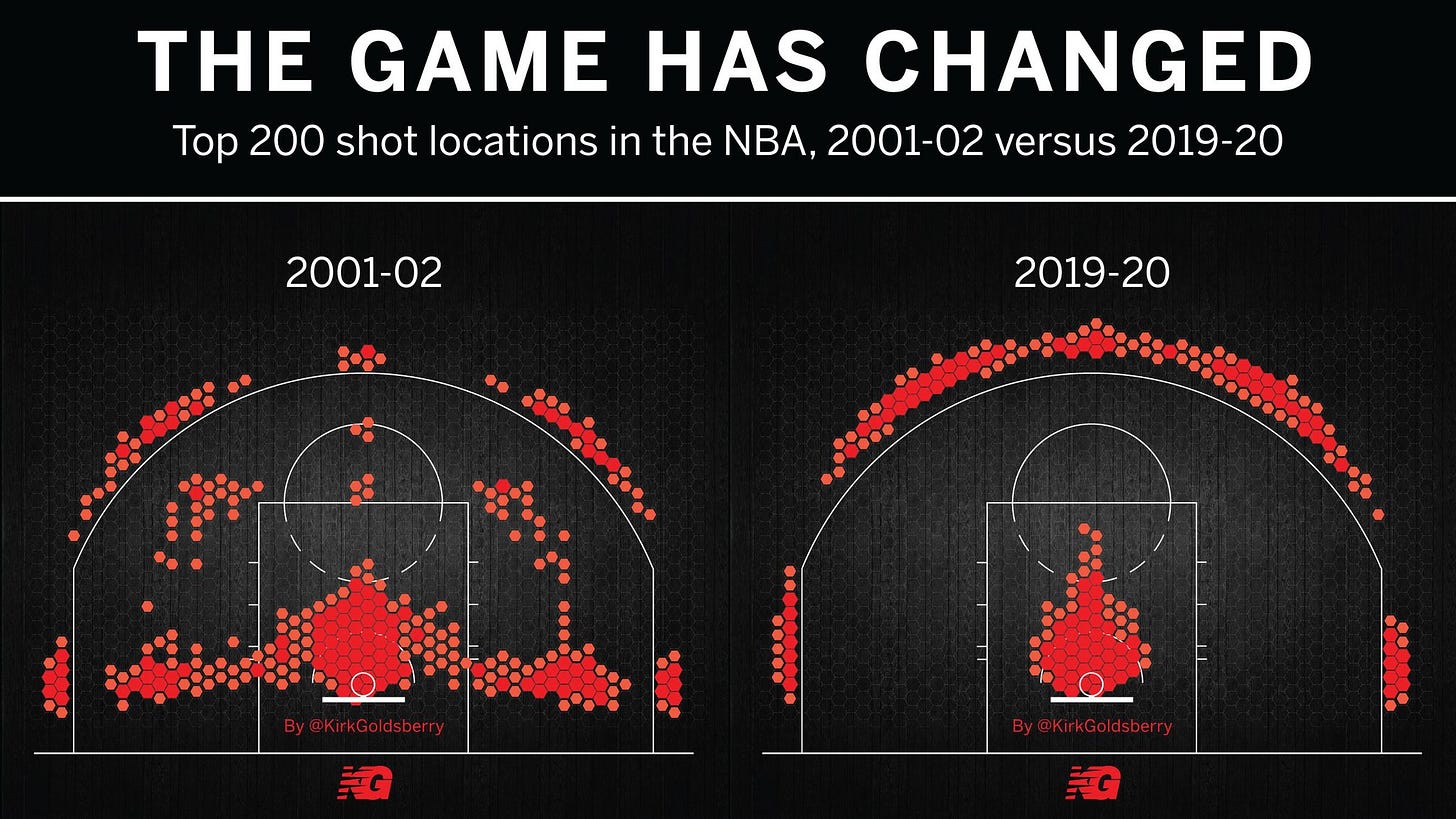

Because what first came to mind when I saw this graphic is index funds. Maybe that means I have broken finance brain, but to me the Goldsberry graphic is the sports equivalent of those charts showing assets flowing into passively-managed funds and out of actively-managed vehicles.

Here’s the way the world used to be and here’s the way it is now. Pretty simple.

If the world is getting more connected and more efficient, it only makes sense that strategy hegemony will prevail across disciplines.

As is the case in any game — basketball, football, chess — there are certain conventions that broadly govern gameplay. There are strategies that no team would ever pursue because they are guaranteed losers (or they just don’t make sense), and strategies all teams will expect their opponents to employ in some form.

What Goldsberry’s graphic shows is how the modern NBA has essentially deemed there to be only one answer to any strategy questions that teams would find acceptable: you either try to shoot a three or take a layup on every possession.

As Goldsberry writes in SprawlBall:

When the league added the three-pointer, it did not just massively inflate the value of the 24-footer and the sniper who can drain it, nor did it just massively deflate the value of five-footers, 10-footers, 15-footers, and 20-footers. It also rearranged the value of skill sets and the value of player types. The value of the catch-and-shoot specialist has exploded, while the value of the post player has collapsed.

The scope of what’s now deemed acceptable by conventional NBA tactics is less than half as large as it was two decades ago. The court hasn’t gotten smaller. The value of the shots available at any one time hasn’t changed. It’s just that teams eventually started exploiting the arbitrage opportunity that had been staring them right in the face.

According to Goldsberry’s data, the average shooting percentage from 21-22 feet is 39% while the average shooting percentage from 22-23 feet is 38%. But the shot from 22-23 feet is worth 50% more if you take it along the baseline. So why would anyone ever shoot from 21 feet? The extra foot is basically a free lunch!

And so the NBA ate it.

And because people with hammers only see nails, I also interpreted Goldsberry’s graphic as something like an extension of what we discussed last week: the idea of everyone knowing everything.

If the NBA equivalent of “knowing everything” means that it is, on average, a stupid decision to do anything other than pursue a three-pointer or a layup, the investing equivalent has become spending more than the bare minimum on fees. The chart above from BofA isn’t really about investing style preferences, per se, but about which strategies allow investors to lower their fees.

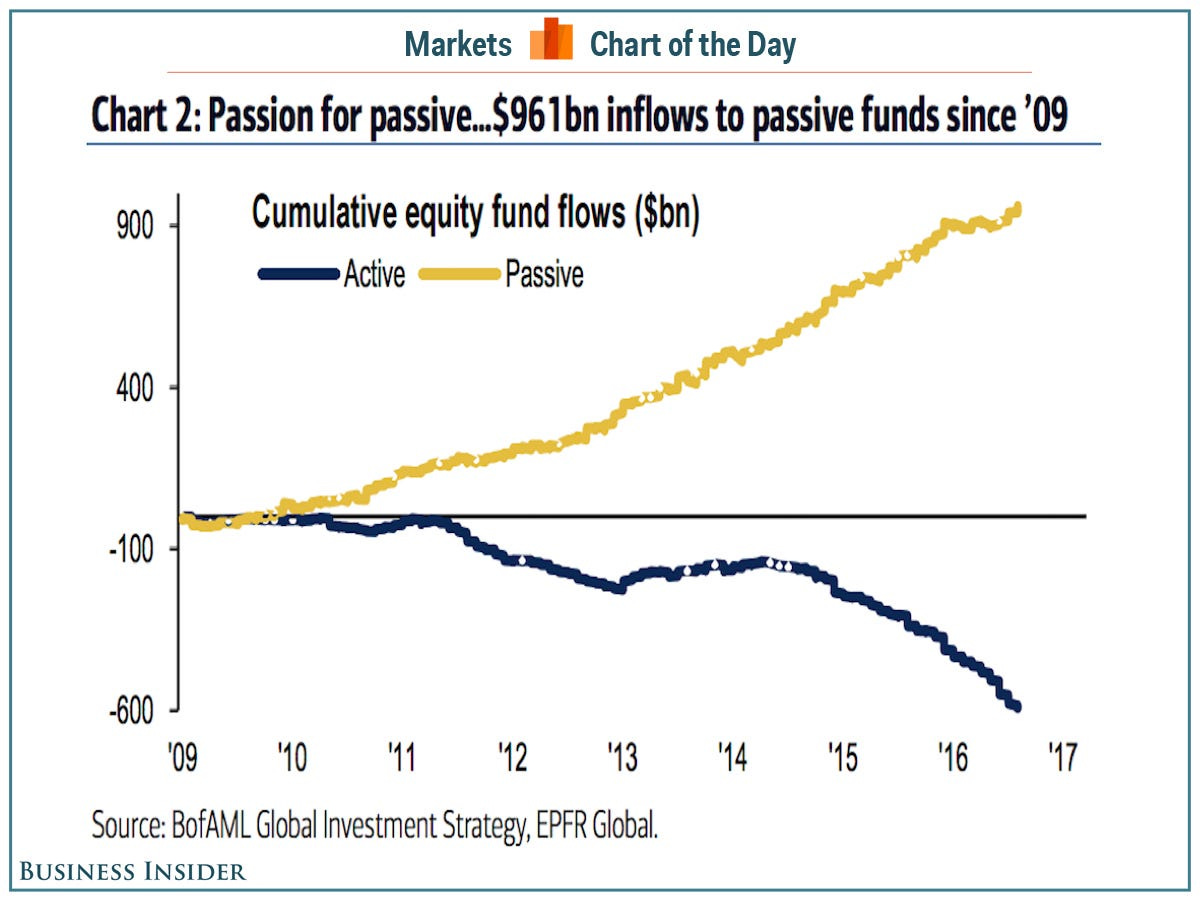

Data from Vanguard shows that taking the average fee paid on an investment portfolio from 90 basis points to 25 basis points can save an investor nearly $100,000 over the lifetime of the portfolio. (The chart assumes a $100,000 starting balance and a 6% annual return, which is reinvested.)

For the average investor, the answer to the question “what should I do with my money” is simple: whatever is cheapest.

For an average basketball team, the answer to the question “how should I try to score the most points” is similarly pat: take threes and layups.

And what’s most striking about Goldsberry’s graphic is how much the dispersion has narrowed. If you look at the dark red areas of Goldsberry’s graphic, you can see that the number of areas with this coloring has dropped from 9 to 6. But if you really drill down into what’s happening along the baseline and the elbow, there were more like 13 distinct hot spots on a 2001-era NBA court, more than double the number that exists on today’s floor.

The decreasing breadth of what is deemed an acceptable shot by professional basketball players also looks a bit to me like the declining number of publicly-traded companies. Players and investors are left with fewer options, but their remaining choices are more efficient.

Back in 2017 I wrote about work from Michael Mauboussin — then at Credit Suisse — that explored the shrinking number of companies listed publicly. At the end of 2019, for example, the Wilshire 5000 actually had 3,473 members. The index hasn’t had 5,000 constituents since the end of 2005.

And as Mauboussin’s data shows, the overall vibrancy of stocks joining and leaving the public market has been on the decline for two decades.

Less choice when it comes to choosing investments might seem constraining to investors in the same way that fewer analytically-approved shots straightjacket pro basketball players.

But as Mauboussin notes, the declining number of constituents in the stock market leaves investors buying companies that are “bigger, older, and in more concentrated sectors than two decades ago… This likely contributes to public markets that are more informationally efficient than ever before.”

Again, we see the theme of less absolute choice available to players and investors but what remains on the menu is deliberate and measured for more likely success.

Here’s how I concluded my piece in 2017:

As a result of the stock market’s decline in popularity, asset classes like private equity and venture capital have risen in popularity. But as these asset classes gained popularity amid an increasingly efficient public market environment, so too did returns in these spaces decline.

“Venture capital funds launched in the 1990s outperformed public markets,” Mauboussin writes.

“But funds started since 2000 have underperformed public markets, with an improvement in recent years. Buyout funds with vintage years before 2006 outperformed public markets, but those launched in the last decade have only equaled the returns of the market. Hedge funds have also seen diminishing excess returns in the past decade.”

The overall upshot here is that investing is both as easy and as hard as it has ever been.

ETFs and the changing character of the stock market — towards larger, more profitable, and more mature businesses — benefit investors who are seeking low-cost exposure to assets likely to outperform cash and Treasuries over time. Institutional investors looking to hedge riskier, more concentrated bets can now turn to the stock market for this need.

But outperforming your peers, either in the stock market or in spaces like private equity and venture capital, has now become an even more difficult prospect.

These themes have accelerated.

Since this piece was published, the five biggest companies in the S&P 500 have increased their relative weighting in the index from under 12% to more than 17%, as this chart from Bespoke Investment Group show.

Professional basketball is seeing a similar increase in the trend towards a more universal three-and-layup approach.

In the 2001-02 season, around 18% of shots during an NBA game were from three; in the 2017-18 season, more than 33% of shots were threes, as Goldsberry’s chart shows.

And I think this codification of what works and what doesn’t has pushed the sports and investing worlds to somewhat similar places in recent years.

Conventional strategies had endured because they fit the framework of “how things have been done.” But increasing information efficiency allows for less room to argue that because something “feels right” or “looks right” it’s a viable strategy.

Goldsberry’s book chronicles the death of the low block post-up game. Mauboussin’s work chronicles the death of active management.

Both are dying at accelerating rates.

And both disciplines are in a place where the games are basically solved, where just about every participant knows the right answer to every scenario, leaving edges available only to the highest-volume players or those who take their chances cheating.

The uncovering of these more efficient ways to approach investing and basketball are, of course, unlocked by technology. And they are but two small examples of the ways we see previously ignored approaches to problem solving becoming consensus.

And so while in many ways our digitally-enhanced world frees us up to make connections that had previously been only pipe dream intuitions, sometimes it seems things are left looking more uniform than ever before.

Thanks for reading I’m Late to This. If you liked what you read, share it with a friend and make sure to subscribe.

If you agree, disagree, or just want to weigh in on today’s newsletter, reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland. Feedback is always welcome and highly encouraged.