The IMF, live sports, big business, and debates

Four notes on where we stand, where we're going, second- and third-order negative impacts, and who gets to be right.

When I started this newsletter in November 2019, the conceit was that I’d write weekly about one topic I’ve been thinking about but that is in the background of day-to-day news. Hence, I’m Late to This.

As 2020 got underway, I began, for better or worse, to think of this as a “newsletter on business trends” that offered context and cohesion to the seemingly scattershot everyday news cycle. I spent three straight issues in January writing about how everything seems the same.

And then coronavirus happened. I wrote about that a few different ways. But now I want to get back to writing about business-adjacent things I’m interested in and not write personal essays about my own fears.

This is week’s letter is still, however, mostly about coronavirus. Because literally everything is.

But instead of one essay this week I’m going to take on a few different topics at shorter length than a normal letter. I enjoy writing this weekly and don’t plan to increase the cadence to publishing multiple times per week. But if I were to write, say, 3 or 4 times per week, each of these sections is about what would be feasible to publish daily.

This week I’m going to look at:

Big business getting bigger

How the return of sports covers up challenges for scripted content

What college athletic departments and the IMF have in common

Coronavirus as the force to settle every debate

If you haven’t yet, make sure to sign up below so you never miss an issue. We publish every Sunday morning.

And if you want to agree, disagree, or engage on any of the topics discussed in this letter just reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter @MylesUdland. Feedback is always welcome and highly encouraged.

The bigger the better

This past week felt like a turning point of sorts.

The data started getting better in the hardest hit parts of the world: Italy, Spain, New York. The number of deaths is shocking, but deaths lag. The absolute number of people getting sick is slowing. The curve is bending.

And with this development has come a sense that it is time, finally, to start really thinking about what comes next.

What does life look like when we’re allowed to go outside? How do we stay safe? Who got sick last month? Who is still sick? And when you’re stuck inside for two or three months and then told it’s time to run free, where do you even go?

And so as we contemplate our collective next move here in the U.S., attention is focused on which institutions — which pillars of American life — will be opened first. And how we proceed is probably found in something like the plans outlined by big businesses that never closed at all.

Walmart’s CEO Doug McMillon went on the TODAY Show on Friday and as Conor Sen noted, his commentary probably does more to sketch out what the next few quarters look like than where the administration is at right now.

But that Walmart is leading the way on our economy re-opening is a bitter pill. This is a company with as many financial and human resources as any company in the world. Of course they are able to create a “new normal” on the fly and make its employees and customers feel like the economy is re-opening.

Going to Walmart, however, is not an experience that is widely cherished. It’s a necessity, essential. It’s a chore: we need the stuff Walmart sells to survive more than flourish.[1]

And after a decade of being told that experiences are to be valued more highly than things, looking at a future in which a “re-opened” economy means Walmart, McDonald’s, Chili’s, Costco, and Dick’s Sporting Goods are open while any local restaurant or shop of interest stays closed or goes out of business doesn’t have great appeal. It doesn’t really feel like winning.

And it’s a reminder that “re-open” ought remain in quotes, because it’s going to be but a sad imitation of the economic life we lived a few months ago. The drumbeat of an economic “re-opening” is starting to get louder, but I don’t think we’ve thought all that hard about what “re-opening” actually is. Which isn’t all that different than how we got here.

A few weeks ago all we wanted to do was flatten the curve. To most people the “what for” part of that plan didn’t make sense and maybe never did. But, nevertheless, the curves are flattening. Maybe knowing why you’re doing something is overrated.

Watch what’s not live

A little over a week ago I was sure that sports would not come back until events could be normal.

You know: fans in the stands, sitting close to each other, cheering loudly, not wearing masks, drinking beer, and so on. Rich Greenfield told me this was a bad take. It only took a week for him to be right and me to be wrong.

This week, we saw the golf world announce its path back. Baseball trial-ballooned an “everyone come hang out in Arizona in August” plan but seems to be trending towards something more workable. The NFL draft is in less than two weeks and the football world broadly seems to think their September start dates will allow the sport to proceed along semi-normal lines.

And the short of all this news is that sports are coming to a television near you soon.

Now, everyone is going to have their own definition of “normal” on the other side of this. But if the average professional sports event looking like it did circa 2019 is “normal” then the sports world will probably be the last piece of American life to find that prior level.

It seems then that sports will be among the first pieces of the cultural puzzle to fall back into place as things tentatively restart but one of the last areas to get all the way back to whatever was normal last year.

But we’ve also probably spent too much time thinking about sports as a marker for normalization in general. Getting teams in shape and verifying their health before airing games is relatively easy. And I stress: relatively.

It’s at least easier than rebooting production for a scripted show that has fallen behind its production schedule by several months. Scripted shows and movies bring together high-powered talent and low-level grunts, union and non-union workers, and keeping those sets controlled, clean, and contained is a far harder task than gathering staff that all works for one organization.

Professional sports teams have had tabs on their players during this entire episode; who knows where your cast and crew scattered to, who they’ve been in touch with, who stayed healthy or got sick and so on when production was abruptly shutdown in March.

The product itself also suffers less — again, on a relative basis — if you’re doing a half-version of what had been previously live. Sure, you could take all the footage you’ve got from a movie shoot or the first 14.5 episodes of a 22 episode season and just edit things together so there is something to put on television or sell for PPV. But lower quality experiences watching a sporting event or a late night talk show will be tolerated far more than a janky cut of the next season of Succession.

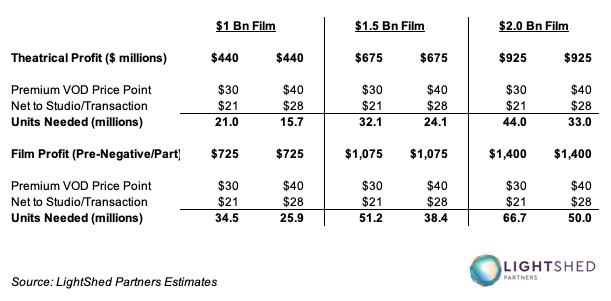

So if the challenges facing live events have been over-discussed in the future of content conversation, then what scripted content looks like in six months has been under analyzed. I think some of us are taking for granted that movies, for example, have value when you just release them on Disney+ or whatever. Lightshed has a great breakdown on this in a note from last month.

The firm adds:

Looking just at replacing theatrical gross profit means 16-21 million units sold for a $1 billion movie all the way up to 33-44 million units for a $2 billion box office film.

And the units needed to be sold above assume zero marketing spend, which is obviously absurd. It would likely have to be tens of millions of premium video on demand marketing spend, which further increases the number of units sold. Simplistically for every $50 million of marketing spend, it increases the units needed by another ~2 million. You quickly realize just how big the PVOD transactions need to be for the math to work for a studio.

Not great.

On the one hand, it’s harder to notice real-time changes in a product that isn’t live. On the other hand, the cadence of producing, editing, marketing, and airing canned shows and movies is part of a precision supply chain just like toilet paper and Clorox wipes.

And every funnel is under pressure right.

Fiscal austerity, student-athlete style

Unlike their professional counterparts, some college administrators aren’t so sure that staging games in empty venues will work.

But universities not making any money from their most lucrative sports also doesn’t work.

The AP published a story earlier this month about the financial crisis facing athletic departments in the wake of the NCAA tournament’s cancellation. It’s brutal.

Canceling the men’s Division I basketball tournament cost the NCAA $375 million it was scheduled to distribute to its member schools.

Asked for their worst-case scenario analysis, 65% of the athletic directors said revenue for the 2019-20 fiscal year would drop from 0-20%, including 35% expecting a decrease ranging from 0-10%.

Some schools are already taking steps to deal with this year’s shortfalls.

Trying to make up $5 million in lost revenue from basketball tournament cancellations, Iowa State has announced a one-year, temporary pay reduction for coaches and certain staff to save more than $3 million. The school will also suspend bonuses for coaches for a year to save an additional $1 million.

That article was published on April 2. The situation has not improved. And this is only starting to account for the potential consequences of a football season that can’t start on time.

I had a cup of coffee in Division I athletics and the shoestring workings of non-revenue sports (read: not football or basketball) at major schools would shock those who only see college sports as the largesse of an Alabama football game or the Final Four.

College athletic departments are run like a country in an IMF program. The austerity comes top-down and those with the most limited ability to cut costs are required to slim down first.

Superficially, most college athletic departments appear flush. In reality, most are just barely keeping it together. I worry that many vulnerable Olympic sport teams at major universities will be on the chopping block on the other side of this.

And the financial problems come from two directions — the conferences and the NCAA.

The NCAA, as an organization, really only makes money one time a year. And that is during March Madness. Every other television deal is negotiated directly between the conferences and the networks. The NCAA is cut out.

Member schools in the SEC, Big Ten, and so on get a slice of their conference’s deal with Disney, Fox, and other broadcast partners. Ticket sales at Michigan versus ticket sales at Rutgers football games create inequality between members of the same conference — as do the broad financial positions of the universities, etc. — but the reason Rutgers joined the Big Ten so its football team could be ritually sacrificed each week is because of the share of the Big Ten’s TV revenue the school gets. Even if that cut is delayed and smaller than expected. And so these schools need football to be played in the fall, stadiums full or not, because they need the money that TV networks have agreed to pay them.

Now, some of this TV money trickles down to the Olympic sports by way of improved facilities, apparel deals, discretionary spending for travel, and so on. But the NCAA itself is responsible for putting on championship tournaments for every sport except football.[2] And by “putting on” I mean, the NCAA pays for everything including you getting from your campus to the event.

In the grand scheme, the amount of money it costs to run, say, the cross country national championship race or the field hockey championship tournament is nothing compared to March Madness.

A temporary shortfall in revenue because March Madness was canceled or the football season might be delayed or major donors are holding back this year seems like the kind of thing that shouldn’t put at risk an entire sport’s existence at a major university.

But we all know what happens when the IMF comes to town.

Soon we can all stop fighting

In an interview on Patrick O'Shaughnessy’s Invest Like the Best podcast this week, Gavin Baker made the point that part of what’s exciting about this current moment is that many, many investing debates are just going to be settled.

When huge dislocations happen in markets, all the hypothetical debates about which asset classes stink, what styles work, and which companies are well positioned to take market share in the future stop being hypothetical.

I’m excited, because there have been all these hotly debated topics around different business models, most of them tech-enabled — whether it’s space-as-a-service, iBuying, are fintechs better at lending than traditional financial institutions — and they’re all going to be resolved!

We’re going to know the answer to some of the most hotly debated topics within the world of technology investing over the last ten years and we’re going to know those answers quickly. [...]

Another thing much debated: Is sports really the anchor of the linear TV bundle? Well, we’re actually going to find out this month and next. Full stop.[3]

So we no longer need another Stratechery piece on whether sports rights are enough to make the cable bundle viable long-term. All we need to do is wait.[4]

I think sports coming back to TV with no fans is going to be less interesting than what seems to me like the consensus view that ratings will be huge because we’re so starved for content. Watching what amounts to a closed scrimmage isn’t exactly appealing and probably leaves me more interested in my Madden franchise. A fan-less sporting event happening in a vacuum makes my simulated team in a video game seem more real, not less.

But, again, no need to keep going on this: we’ll know the answer soon!

And we can take another debate like government spending. Readers know where I fall on this. The “debate” about the U.S. government’s default fiscal stance was always fabricated and based on an ideological position about running governments like households or businesses even though the entities share nothing in common. To my mind, this issue has also been settled during this crisis.

Never again do we need to seriously listen to the fiscal hawks who believe the deficit “will matter one day” because if it’s going to matter — meaning that borrowing costs will rise meaningfully for the U.S. government as result of an imbalanced budget — the market isn’t going to wait to express that view. And the signal right now is that there is a lot of excess fiscal room. We should use it.

And while Gavin’s construction focuses more on things that were being actively debated three months ago, this framework also proves useful in thinking through what consensus truths we might abandon after this crisis period.

Which brings me back to an idea we talked around earlier — millennials valuing experiences over stuff. This notion is the defining consumer phrase of the post-crisis world we’ve lived in for a decade and that we are exiting now.

The disappointment in Walmart and McDonald’s opening first after the crisis is not because of the products these companies sell — which are great — but that so much economic and cultural energy has gone into finding more interesting alternatives for spending our money.

And sure, mass-produced stuff is kind of dumb. I don’t need another television, even if it seems like they’re giving them away. And as someone who is afraid of flying and generally anxious about travel, I will concede that going to a new place is great. Once I actually get somewhere I’m almost always glad I went. Experiences are pretty good! And often better than more stuff.

But it’s not entirely clear that the millennial generation ever made a collective, coherent value judgment on experiences being better than things. This isn’t the future anyone asked for, merely the one we got.

And over time, “stuff” grew to be an increasingly broad category that ultimately served as a stand-in for “anything Boomers took for granted.” These “things” morphed from clothing and accessories and meals away from home — the traditional categories taken up by excess disposable income — to housing, general upward mobility, career security, etc. Anything resembling a decent middle class existence became stuff.

Selling this “experiences over things” narrative justified why there just didn’t seem to be much opportunity available to young people in the wake of the financial crisis.

The debate, as it were, is whether the experiences over stuff dynamic is a real lifestyle choice made by an entire generation or just a convenient position for lawmakers pushing sclerotic policies to stake out and a marketing gimmick for a new generation of companies that see “experiences” as a category broadly ripe for disintermediation.

I know where I fall, but fortunately it doesn’t matter: everyone will get the answer soon.

1: There’s a labor market story here, too. I saw a viral tweet this week that I can’t find which said “from unskilled labor to essential employees in one pandemic.” This is the whole story. Working at Walmart or in an Amazon warehouse should be a $50,000/year job. At least.

There’s a lot of buzz about there being a re-industrialization of America after this. I think this view is founded, but that doesn’t mean we should be thinking about opening coking facilities in the Midwest. It means we should pay people who work at CVS and Kroger and Walmart and Amazon $25 an hour. “Manufacturing jobs” is a stand-in for blue collar jobs that offer families a middle class living. What we’re asking essential retail and grocery and pharmacy employees to do right now is exactly that.

2: Note that it is called the “College Football Playoff National Championship,” not the NCAA Title Game. There is no formally recognized NCAA champion for FBS schools.

3: Gavin also includes an interesting discussion about why WeWork provided value to traditional CRE tenants and why there still probably exists an opportunity for WeWork, or maybe another player with better financials, to make the concept work. I agree strongly. But we’ll leave that here for now.

4: If there’s a through-line to this letter it appears to be sports this week. Sort of.